The 14th anniversary of Mr Ward’s horrific prison van death in custody

A Rally in Perth demanding charges to to laid against the perpetrators of Mr Wards Death in Custody

While millions celebrate “Australia Day” around the world this Wednesday, the country's Aboriginal population will be in mourning, just as they have been every year for almost quarter of a millennium. For the family and friends of the late Mr Ian Ward in Western Australia's Pilbara region, the date also carries a more recent sombre significance - namely being the anniversary of his arrest and tragic death in custody in January 2008.

The barbaric circumstances of Mr Ward’s death, and the disturbing details which emerged during the subsequent coronial investigation, are still traumatising to many. The 46-year-old father of four’s life in the Goldfields, Western Australia, touched countless people across Australia. An utmost respected Aboriginal elder, Mr Ward was well-known for his cross-cultural abilities and scientific knowledge, and as a highly skilled hunter assisted many non-Indigenous people to see native wildlife. As an international ambassador for Aboriginal people and representative of his local Ngaanyatjarra lands in Australia and abroad, he fought for many years to have the rights of his people in the Gibson Desert nature reserve recognised.

He was also an advocate of traditional land management techniques, having been heavily involved in land care, and often worked as a guide for a variety of scientists including biologists, botanists, geologists, palaeontologists and geophysicists undertaking geological surveys. He simultaneously worked as an educator of children and as a chairperson and interpreter in transactions relating to native title in his local community, while also being renowned as a dancer and an artist, particularly for his exceptional skills in glassworks and many other art forms.

He was not dangerous.

At the time of his arrest on Invasion Day 2008, Mr Ward had been driving on dirt roads over 1000km for two days, when it became necessary for him to cross a very short strip of gazetted bitumen road to continue his journey by dirt road to an Indigenous camp. Although they later admitted there was nothing untoward about his driving, the police, who were parked with their lights off, stopped and breathalysed him. When found to be over the limit, Mr Ward was asked if he wished to contact a legal representative, to which he replied, “I just want to have a sleep.” He was detained overnight in Laverton Police Station.

That night, before a bail hearing had even been conducted, arrangements were made for security staff to transport him to Kalgoorlie the next day. At approximately 10.15am the following morning, the bail hearing was conducted at the door of Mr Ward’s cell immediately after he had been woken up and was reportedly still half asleep. The justice of the peace, Barrye Thompson, failed to supply prescribed information about bail, instead telling Mr Ward he would be remanded in custody to appear in Kalgoorlie Magistrates Court the following day.

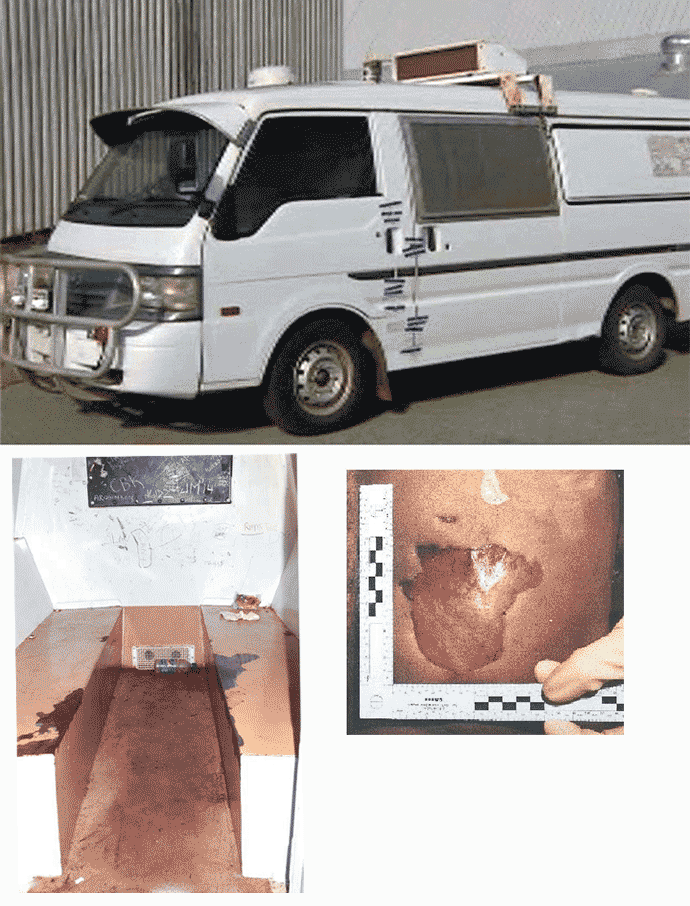

Little over an hour later, then G4S employees Nina Stokoe and Graham Powell arrived. Although Laverton police told them Mr Ward was “very compliant” and would be “no trouble”, they classed him according to an arbitrary company rule that all male remand prisoners taken from police lockups should be regarded as “high risk”. Despite the fact it was approaching the hottest part of a day on which temperatures would soar to 42 degrees, and the prison van they were driving included a middle pod with padded seats, seatbelts and windows that could be opened while still protected by an internal grill, they chose to place Mr Ward in the structurally separate more secure rear pod.

It was of entirely metal construction apart from a closely grilled steel mesh window in the rear outer doors, through which any airflow was prevented by an inner door constructed of thick Perspex. Mr Ward was locked inside the airless steel pod to make the 360km journey to Kalgoorlie in the Goldfields, Western Australia, with nothing more than a 600ml bottle of water and a frozen meat pie.

Although most of the journey passes nothing more than burnt-red desert for miles around with zero shade, neither Stokoe nor Powell checked whether the air-conditioning in the pod was working. They failed to take any rest stops or make any checks on Mr Ward during the journey, which took almost four hours. Both gave evidence that when they had almost reached Kalgoorlie, they heard a “thump”. Powell said he then stopped the vehicle to check on Mr Ward.

He was passed out on the floor of the steel pod, which had no seatbelts to keep him upright. Although the temperature of the cell, which had no working air conditioning, would have reached over 50 degrees inside, Powell said he did not remove him from the van because it was against private security company G4S’s (then GSL) policy to do so unless they were in a secure area. He said he instead threw some water on Mr Ward in an attempt to rouse him, whilst leaving the door chain in place. When he didn’t move, without attempting to offer any assistance, the guards got back into the van and drove to Kalgoorlie Regional Hospital, where Mr Ward was pronounced dead an hour later.

At the inquest, a doctor who assisted in removing Mr Ward from the van, Lucien Lagrange, said it felt “like a blast from a furnace” when he opened the tiny steel pod’s door. Mr Ward’s body, which had a temperature of 41.7 degrees, was unable to be cooled down even after an ice-bath, retaining a core temperature of 41 degrees 35 minutes later. He had suffered third degree burns to his upper torso from falling on the scorching floor inside the steel cell, the surface of which would have reached 56 degrees.

In his report released a year and a half later in June 2009, the state’s coroner, Alistair Hope, found Mr Ward died in “conditions of grossly excessive heat,” describing the pod as “barbaric in appearance” and calling its use for long-distance travel “inhumane”. He criticised the two guards as having “demonstrated a lack of concern as to the prisoner’s welfare” and “a lack of compassion for the deceased.”

The Prison Van where Mr Ward died

The pod contained no intercom or sound warning facilities. Neither guard could remember telling Mr Ward about a small panic button by the door which was not marked or labelled and was even missed by the police forensic officers who first examined the vehicle. Later examination revealed that in sunny weather it was difficult to tell whether the corresponding light in the front of the vehicle was illuminated.

Stokoe claimed in evidence that when she picked Mr Ward up at the station, “It didn’t feel hot in the back of the vehicle when I opened the back doors and the vehicle had been running from Kalgoorlie all the way to Laverton when we stopped,” which she said caused her to assume the air-conditioning had worked on the outward journey. However, she also stated that she told Mr Ward, “The quicker you get in, the quicker the air-conditioner kicks in,” but could not recall any other conversation with him. Hope found the comment indicated “that the pod must have felt uncomfortably warm or hot and in my view Ms Stokoe was attempting to deflect criticism of her performance when she claimed otherwise.”

Stokoe also said in evidence that the surveillance CCTV in the van operated erratically and the picture was poor, but that she checked it intermittently and advised Powell of her observations. In a video interview with police, Powell said Stokoe told him at one stage Mr Ward had taken his shirt off. When questioned, Stokoe denied that Mr Ward took his shirt off at any time but claimed it was unbuttoned when he entered the vehicle. When CCTV evidence at Laverton police station showed Mr Ward entering the prison van with his shirt buttoned up, Stokoe conceded she might have been wrong but persisted in claiming Mr Ward did not take his shirt off at any time.

Although Powell later denied being able to recall Stokoe making the comment, Hope found it “difficult to understand how Powell could have claimed that Stokoe told him that the deceased had taken his shirt off if that event had not taken place,” adding that if Mr Ward did take his shirt off and Stokoe had commented on the fact, she would have been aware of his experiencing a hot environment. He added that if Mr Ward did remove his shirt, as there would have been no reason to put it back on in conditions of extreme heat, only Powell or Stokoe could have put it back on his body, which Hope called “a potentially sinister aspect of the evidence especially if the shirt had been put on in an attempt to conceal their knowledge that the deceased had experienced difficulties during the course of the journey.”

Hope also called it “surprising” that both guards’ accounts of their observations of Mr Ward referred to exactly the same distances, saying, “It is difficult to accept that each witness acting independently gave an identical approximation of the location of these apparently innocuous events in a landscape devoid of significant landmarks.” A re-enactment of the journey on 12 March 2008 in similar weather conditions also brought much of their evidence into question. Both guards claimed Mr Ward was drinking from a water bottle and seemed otherwise normal past Menzies and again looked out of a window about 50km before they reached Kalgoorlie. However, when the re-enactment recorded temperatures of well over 47 degrees in the pod past Menzies, the seat being 48 degrees, Hope found it “difficult to accept that the deceased was not showing some signs of distress in that environment.”

He was highly critical of the two guards, finding both to be unreliable witnesses. “Unfortunately in my view neither witness was a witness of truth and it is not possible to determine precisely what took place when they discovered that the deceased had collapsed,” he wrote, adding, “It would appear that a decision was made by the two officers to provide a concocted story in relation to events with a view to minimising their involvement.”

Family Member of Mr Ward

Hope further criticised the premature arrangement for transport to take Mr Ward to Kalgoorlie prior to the bail hearing commencing, noting he could only be legally transported after a remand warrant was signed by a justice of the peace. He added that if the legislation had been complied with, Mr Ward would not have died when he did, further questioning whether Mr Ward was lawfully in custody when he died given Thompson’s “very poor understanding of his role and responsibilities ... particularly in respect of considerations of bail.” Thompson had been exempted from having to complete justice of the peace training and although he was provided with a manual, admitted he had only read part of it.

Hope’s conclusion was damning: “In my view it is a disgrace that a prisoner in the 21st century, particularly a prisoner who had not been convicted of any crime, was transported for a long distance in high temperatures in this pod.” He found both Stokoe and Powell, their employer G4S and the Department of Corrective Services had all contributed to Mr Ward’s death, adding, “A question which is raised by the case is how a society which would like to think of itself as being civilised, could allow a human being to be transported in such circumstances.”

Despite his findings, both Powell and Stokoe continued to transport prisoners in WA for over a year until public pressure forced G4S to fire them. While Stokoe had been relatively new in the job, Powell was G4S’s most experienced guard. He had been suspended from his supervisor’s role just six months previously for condoning “racial slurs directed at prisoners”, according to G4S company documents, which stated “... he knows it goes on and allows it. In fact he states that he participates in it.”

Although Hope found G4S's vehicle was “not fit for humans”, it retained its contract with the WA government and in September 2009 was reappointed Victoria’s prison transport contractor under a new five-year multimillion-dollar contract, the position never being publicly advertised as stipulated by government guidelines. Shortly after Mr Ward’s death, the company had been fined $100,000 by the WA government for breach of contract, a small price from the world’s largest security company by revenue which according to its website boasts 533,000 personnel in more than 85 countries.

The Van where Mr Ward took his last breath - he was cooked to death whist the prison officers sat in air-conditioned comfort in the front seat

However, it was May 2009 before the Ward family even received an apology from WA Corrective Services, a year and four months after his death. Almost a year later in March 2010, after an Aboriginal Legal Service representative told a rally outside WA’s parliament that it had repeatedly written to the government since July 2008 calling for an ex-gratia payment, State Attorney General Christian Porter announced an interim ex-gratia payment of just $200,000 to Mr Ward’s widow. The then Australian Labour Party shadow Attorney General John Quigley subsequently ran a public campaign, resulting in the family receiving an additional ex-gratia payment of $3million in July 2010. However the compensation was of little comfort, coming just weeks after WA’s Director of Public Prosecutions, Joseph McGrath, travelled to Warburton to tell Mr Ward’s family the prospect of criminal charges was non-existent due to “lack of evidence”.

“We just cried and cried and cried,” said Mr Ward’s cousin, Daisy Ward. “The DPP flew to Warburton to tell us that they were not being charged. We’re really down and out thinking of what happened. We don’t feel happy just thinking the horrible thing that they didn’t care who was in the back of the van. They had a duty of care and they didn’t do it [sic].” In fact, when McGrath arrived in Warburton to tell the family a prima facie case did not exist, none of Mr Ward’s family was present except for his widow, Nancy, and a young niece who happened to be visiting at the time. Although Nancy had been told of the quickly arranged visit by McGrath, she had no legal representation as the ALS had not been advised of the timing of the trip.

While the legal representatives of all parties to the coronial inquiry were contacted by the McGrath prior to his public press release on 28 June 2010, most of Mr Ward’s family were the last to know. Daisy and Mr Ward’s brother, Richard, were over 300km away on cultural business, while Mr Ward’s mothers, his late father’s five wives, were at Patjarr some 320km to the north. It was left up to a family friend, Jan Turner, to contact Daisy and Richard, who then went to Patjarr to tell the mothers.

McGrath’s press release stated that: “Case law emphasises a very high degree of negligence is required for conduct to amount to manslaughter. I do not believe that the evidence is such that a jury could find ... that either Ms Stokoe or Mr Powell was criminally negligent to an extent that was gross, culpable or complete. Nor do I believe the State could successfully rebut a defence which relied on a defence of honest and reasonable mistake.”

Devastated by the decision, the Ward family, many of whom speak next to no English, nominated Daisy as having the best language and cross-cultural skills to travel to Perth to ask Porter and McGrath to explain why charges are not being laid. “I saw him [Porter] and talked about it,” said Daisy. “Now I’m waiting for the DPP to get back to me, waiting just to ask why they’re not being charged when they left my brother to die in the back of the van. They made a lot of mistakes – too many mistakes. They never checked the tyre - there was no spare tyre. There was no air-conditioning. It was a rusty looking thing. They never checked.”

With no audio or video recording of what occurred during the journey, McGrath relied entirely on Stokoe and Powell’s evidence in reaching his decision. However, irregularities in the police investigation meant the two guards and their supervisor were given the opportunity to collude prior to any statements being taken. A spokesperson for WA’s Deaths in Custody Watch Committee, Marc Newhouse, said of McGrath’s conclusion, “My understanding is that he came to the decision after having looked at the guards, the company and the Department of Corrective Services. The evidence was diluted because so many different parties are involved, and he came to the view that there simply wasn’t enough evidence to bring a criminal case against any one party.”

“The guards were clearly negligent,” Newhouse continued. “They didn’t meet their duty of care. However, if they were charged, G4S and Corrective Services could simply say ‘It was nothing to do with us’, so the bare minimum is that they should terminate the contract and return responsibility to Corrective Services. At least then, if there’s one party responsible, the next time something like this happens charges can be laid.”

Newhouse criticised the fact Mr Ward was ever taken into custody as a drink-driver. “The key recommendations of the Royal Commission were that less Aboriginal people should be taken into custody and prison should only be used as a last resort. However, the situation in WA is that there are a lot of people in prison for driving offences. Our prisons are dangerously overcrowded. The system that they’re working with has created conditions where prisoners rights are being breached on a daily basis, meaning a petty offence can result in a death sentence. We’ve gone backwards since the Commission, absolutely.”

Newhouse blamed institutional racism for the failure to properly investigate many deaths in custody. “There’s a denial by people in key positions, such as the police commissioner and the Department of Corrective Services, that institutional racism against Aboriginal people exists to warrant investigations,” he said. “I absolutely disagree.”

One of the many Rallies in Perth calling for justice for Mr Wards death

In the aftermath of Mr Ward’s death, the Deaths in Custody Watch Committee subsequently ran a campaign for safer prisoner transport and seeking an end to the privatisation of custodial services, which called for the use of air transport or video conferencing instead of long road journeys, medical checks for detainees prior to transportation and immediate upgrades and regular checks of transport vehicles. The Legislative Council of Western Australia in turn resolved to consider the feasibility of such air transport and video conferencing for detainees, and to examine and report on the extent to which problems identified by Hope were remedied and the scope and efficacy of any government measures implemented to reduce incarceration rates and prevent further deaths in custody.

One such measure was the replacement of 40 prisoner transport vehicles, a process which only reached completion in December 2010, almost three years after Mr Ward’s death. While the Department of Corrective Services also claimed to have implemented a wide range of measures relating to the transport of prisoners, over two years after Mr Ward’s death in March 2010 46-year-old Aboriginal prisoner James Yarran, an insulin-dependent diabetic, collapsed from heat exhaustion in 41 degree heat in the back of a prison van similar to the one in which Mr Ward died. Yarran passed out on the way back to Perth’s Casuarina prison from a family funeral 31km away, which had lasted four hours in hot weather conditions. Prison guards attended to Yarran and took him to Royal Perth Hospital for treatment before he was discharged.

In a Four Corners investigation into Mr Ward’s death in June 2009, former Inspector of Custodial Services, Richard Harding, who retired from his eight-year position in July 2008, said: “I twice notified the minister in general terms of my great concern about the health, safety and welfare of passengers in the circumstances of these long transports in which I believe were unsuitable vehicles ... but this didn’t sufficiently resonate and nothing much was done at the time.”

As far back as 2001, Harding had noticed a group of disoriented, dehydrated and distressed Aboriginal men being unloaded from a prisoner vehicle after a journey of over 1000km to a jail in Broome. According to Harding, there was “no opportunity to urinate during the journey, very little access to water, poor climate control - it’s beyond belief that those conditions were still in existence, and it did strike me even then that as the overwhelming majority of the passengers were Aboriginal, there was a structural racist element in this and that’s a view that has been certainly reinforced over the years.”

Harding produced a report later that year warning of the dangers and the inhumanity of the system he had inspected. Of the Department of Corrective Services’s inaction since the report, Harding said, “... it actually makes them criminally negligent ... If there were something called bureaucratic manslaughter, the Department of Corrective Services would certainly be prima facie guilty of that.”

The Department of Corrective Services was contacted by this writer but declined to comment. When similarly contacted for comment on Mr Ward’s arrest, WA police stated they were unable to do so as the case had already been dealt with by the Coroner’s Court.

Only in August 2011, more than three and a half years following Mr Ward’s death, were G4S and WA’s Department of Corrective Services finally held to account. However despite both being charged for “failing to ensure the safety of a non-employee in custody”, a charge which carries a maximum penalty of $400,000, Kalgoorlie Magistrates Court fined each just $285,000, with orders to pay court costs of $11,088 and $15,000 respectively.

The following month, Worksafe laid individual charges against Powell and Stokoe for "failing to take reasonable care of a person in custody”. Again, despite the charge carrying a maximum penalty of $20,000, Powell was fined just $9,000, and Stokoe only $11,000. At the time of Mr Ward’s death, a WorkSafe investigation was considered inappropriate because stronger charges were available under police investigation legislation. When WorkSafe announced in January 2011 that it would be laying charges against the four parties for breaches of the Occupational Safety and Health Act, many argued that even the maximum penalties possible under the Act would be inadequate, given the barbaric circumstances of Mr Ward’s death.

Both Powell and Stokoe had initially pleaded not guilty but later changed their pleas after negotiations with WorkSafe. At Stokoe’s sentencing, magistrate Greg Ben reportedly questioned her remorse after she claimed she could not speak to Mr Ward because she thought white women were not permitted to speak to Aboriginal elders, calling the assertion “an insult” to both the court and to the Ward family.

McGrath’s refusal to lay charges against those Hope found responsible for Mr Ward’s death understandably exacerbated many Aboriginal people's lack of faith in the justice system. The subsequent imposition of such moderate fines led many to believe a culture of impunity is giving custodial staff free licence to commit misconduct. Considering the evidence given by Stokoe and Powell, one cannot help but have similar concerns.

Warriors of the Aboriginal Resistance (WAR) Meriki Onus, at an Aboriginal Deaths in Custody Rally in Melbourne 2018

With Indigenous people currently representing 28% of Australia’s adult prisoners, despite comprising just 2% of the overall adult population, Aboriginal Australians are statistically the most jailed race in the world. The national imprisonment rate for Aboriginal adults is 14 times higher than for non-Indigenous people - in WA, where Mr Ward lived, it’s 20 times higher. Aboriginal males are currently incarcerated at a rate five times higher than that of black South African males at the peak of apartheid – in WA, that rate is eight times higher. Almost three quarters of Indigenous adult prisoners have had a prior adult imprisonment. An ominously high number of Aboriginal deaths in custody corresponds with the disproportionate incarceration rates, most of which occur after imprisonment for minor offences, such as public drunkenness, breach of bail conditions, fine default, disorderly conduct, vagrancy, property offences and, as in the case of Mr Ward, driving offences.

There has never been a successful conviction in Australia over a death in custody - either Indigenous or non-Indigenous. However most non-Indigenous Australians are given the opportunity to fulfil their potential, while the everyday candid denial of even the most basic human rights of generation upon generation of Indigenous people keeps in motion a perpetual cycle of destruction that has been in place in Australia's legal system since colonisation. This has morphed from being implemented overtly - for example through the White Australia Policy, the removal of Aboriginal children, and denial of basic citizenship rights such as the right to vote and welfare until the 1960s - into more structural forms, such as the current criminal justice system. The over-representation of Indigenous Australians in prison is clearly connected with socio-economic disadvantage which is in turn compounded by the various racist policies inflicted since colonisation.

For Mr Ward's family - and Australia's Aboriginal population in general - to receive any justice, the details of his death should not be allowed to be forgotten, particularly by those who still think it’s appropriate to celebrate “Australia Day”, a date which represents the beginning of an ongoing attempted genocide of the country’s Indigenous people. For when confronted with the evidence, can anyone honestly need to ask themselves - were both officers really so negligent not to think to check, or did they just not care?

- By Emma Purdy, 25 January 2022

Emma Purdy is an Irish journalist who spent considerable time in Australia researching Indigenous issues, with a particular focus on Aboriginal deaths in custody. An earlier version of this article was originally published in the National Indigenous Times in November 2011.