The bone collectors: a brutal chapter in Australia's past

A discovery has found that DNA Research may help reconnect unidentified First Nations remains Read More (28/12/18). , but even more hope comes from the 'Cape York Map' which identifies the chemical signatures contained in soil, water, plants and animals leached from ancient rocks. Read More (6/3/19) A Research team who have spent the past five years assembling a database of the thousands of sets of Aboriginal human remains still stored in museums and private collections across the world have secured $750,000 in funding from the Australian Research Council to take a deep-dive into the murky world of the commercial trade in human remains further . More here (15/9/21).

The remains of a huge number of First Nations people, dug up from sacred ground and once displayed in museums all over the world are slowly returning, but many and stored in a Canberra warehouse because there isn't enough evidence to find their correct 'Country' for reburial.

Many were victims of defending traditional lands on the pastoral frontier's and colonial troops, paramilitary police forces, settler militia and raiding parties. Their remains were dug up by bone collectors and sold, or bodies cut into parts to satisfy the trade of highly sought-after antiquities in cultural, medical and educational institutions across the US, Britain and continental Europe.

CULTURAL WARNING

Mitchell sprawls untidily across Canberra's grassy northern plain. You would never go there incidentally; there's always a reason. Most of us who have lived in Canberra for any time have stood out there amid whipping winds or under a baking sun at the Australian capital's biggest cemetery. Thousands of precisely trimmed rose and rosemary bushes, plaques and headstones are set in an ocean of lawn, surrounding a constantly exhaling redbrick crematorium.

Colonial explorer and surveyor Thomas Mitchell had quite some bother with the Aboriginal people during his tours into the heart of New South Wales in the mid-1830s. He was rather too eager to shoot on sight than appease the tribesmen, killing seven and drawing mild admonishment from the colonial authorities. Still, Mitchell won a knighthood. Later, a cockatoo – the Major Mitchell – was named after him. And a highway, a river, a town in Queensland, and this ramshackle place in Canberra.

Mitchell is also the unlikely repository for some of Australia's cultural treasure. The National Museum of Australia stands a few kilometres away on the northern bank of Lake Burley Griffin, on what is still a sacred meeting site. The museum has some 200,000 items in its collection, but only a fraction are ever displayed; the rest are stored in two vast, hangar–like warehouses at Mitchell, waiting their turn.

In early 2012, I had arranged to have a look around while researching a book about Canberra. My guides, including senior curator and anthropologist Michael Pickering, opened and slid out for me countless humidity-controlled cupboards and deep drawers containing precious items in tissue paper: botanist Joseph Banks's 18th-century florilegium engravings, convict "love pennies" (coins filed flat by convicts about to be transported from England to the colony, inscribed with messages), breastplates given by white settlers to "tamed" Aboriginal people, convict leg irons.

They pointed out bigger objects: a Play School flower clock; a receiver from Honeysuckle Creek tracking station (remember the film The Dish?); the wheel of the first vessel to dock Vietnamese "boat people" in Australia in 1978. The museum even owns the pink outfit worn by baby Azaria Chamberlain, whose mother was accused of lying when she claimed that a dingo had taken her baby.

I was drawn to a few jars containing some of the museum's "wet specimens". These include animal embryos – platypus and wallaby – and specific body parts of other mammals, such as the arm of a koala. There is the odd human organ, too. I wanted to know more, and asked Pickering to explain. "It is not just about safekeeping treasures here," he began. "We are also the custodians of some great responsibilities."

Many months of discussions and email exchanges with senior museum staff later, I am standing inside a large office deep inside one of the warehouses. The expansive workbenches are clutter-free, save for a few parcels of Aboriginal artefacts. On the walls are anatomical charts. The office is functional, exuding efficient workmanship. But knowing what I do, I infer a sombre, if not quite funereal, purpose to the place.

In line with one of the many security measures relating to this innocuous-looking office, I sign in. Some whose names are in the visitors' book have come here to visit and claim dead ancestors. David Kaus, a softly spoken curator who manages the repatriation unit, punches the code and opens a door into a dark room. There are a couple of tables and rows of storage shelves, several closed cabinets with sliding trays. The open shelves are stacked neatly with "museum quality" (non-acidic and chemical-free) cardboard boxes. Some are like shoeboxes, others resemble boxes in which 100 long-stemmed roses might arrive. Some are short and deep. A small label on one reads:

NMA

Ancestral Remains to be repatriated to

Provenance (NSW) Tharawal

Remains CRANIUM skull

Age Adult

Sex Male

The skull belongs to Kanabygal, an Aboriginal warrior who died when troops shot and beheaded him in New South Wales in 1816. Kanabygal's skull was among the remains of 725 Aboriginal people held here. Many, like Kanabygal, were victims of defending traditional lands on the pastoral frontier – and colonial troops, paramilitary police forces, settler militia and raiding parties. Their bodies were cut up for parts that became sought-after antiquities in colonial homesteads across Australia and in cultural, medical and educational institutions across the US, Britain and continental Europe.

Bigge Island, Kimberley WA

Bigge Island, Kimberley WAAccording to national museum records, in recent decades Indigenous remains have been repatriated to the museum from cultural institutions, including museums, educational facilities, medical schools and private collections in Britain, the United States, Sweden and Austria. Other remains from collections in Berlin, at Washington's Smithsonian Museum, Oxford University and London's Natural History Museum have been repatriated directly to Australian Indigenous communities. The federal government, through the Ministry for the Arts, supports the national museum's Indigenous repatriation programme. Other Australian state and territory institutions also hold significant collections of Indigenous remains and sacred artefacts. All have programmes to return them to country. The government estimates that the remains of as many as 900 Indigenous Australians are still held in institutions in the UK, Germany, France, the US and elsewhere.

Some of the other remains held in the boxes at Mitchell (which I'm not permitted, out of deference to the dead, to open) belong to Indigenous Australians who died in colonial institutions – jails, hospitals and asylums – and, scarcely cold, were "anatomised" (a benign euphemism for butchery). Thousands more, who might have died naturally and remained buried, were exhumed en masse.

The collection of bodies at Mitchell is central to a shameful, bleak, little-known narrative that begins at colonisation and reverberates through Australia's unsettled national sovereignty. It extends discomfitingly into the 20th century, and resonates today as an element of ongoing trauma in Aboriginal communities.

It is also a story about those who created an extensive body-parts market in Australia and in leading institutions around the world. Until the mid-20th century, Australia's Aboriginal people were seen as something of a missing link to the prehistoric; as late as 1945, Arnhem Land people were likened to Neanderthals, their bodies studied just like the other fauna that officialdom considered them to be. The renowned amateur anthropologist Charles Mountford promoted a 1945 lecture tour about Aboriginal people in Arnhem Land under the title Australia's Stone Age Men, drawing on a stereotype that had defined the work of Darwinists and phrenologists for 150 years. Phrenology, best described as a pseudo or even voodoo science "of the mind", had created its own prolific market for the body parts – especially heads – of Australian and other indigenous people since the late 18th century. Long after phrenology was widely discredited, Aboriginal skulls were still sought and displayed with the same benign sentiment that one might attach to animal remains. Mountford's expedition removed hundreds of skeletons from sacred sites in Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory. Many made their way to the Smithsonian in Washington DC and were only returned, after considerable resistance, in 2010.

As a university student in the early 1980s and a political journalist for most of the 1990s and beyond, I was aware of the issues surrounding Britain's continental occupation. I had some minor consciousness of widespread violence against Tasmania's Aboriginal people, and I was moved by the shameful stories of the forced removal of Aboriginal children. My research about early Canberra led me to stories of violence against the Aboriginal people of the Limestone Plains: the Aboriginal people speared the stock; the shepherds, convict workers and the settler masters "took" and raped the women, leading to reprisal and counter-reprisal. OnYong, *the last full-blood man of the Ngambri people of the Limestone Plains, died at the end of a rival's spear in about 1850. Settlers dug him up and fashioned a sugar bowl from his skull. *OnYong's descendants believe the sugar bowl remains in a private Canberra collection; the purported collector has never returned my calls.

A picture of OnYong, *

In front of the Aboriginal Embassy in Canberra, there is a sign saying ORIGINAL SOVEREIGNTY. Beside it flies the Aboriginal flag. Most days a fire smoulders directly in front. This confronts visitors as they stand on the steps of the old "wedding cake" Parliament House to take in the vista of clipped lawn and silvery lake, across to the Australian War Memorial, Australia's foremost secular shrine. For decades, the memorial has been Canberra's most popular public institution – its mandate "to assist Australians to remember, interpret and understand the Australian experience of war and its enduring impact on Australian society".

By the most conservative estimates some 20,000 Australian Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders, and at least 2,000 settlers, died in fighting across the Australian frontier from 1788 until the last established massacre of Indigenous Australians at Coniston, Northern Territory, in 1928. The conflicts involved colonial police and soldiers, settler militias and raiding parties. But the memorial refuses to tell the story of Australia's first colonial conflict.

Consecutive memorial directors have referred to the institution's 1980 Act, stipulating that they must tell the story of "wars and war-like operations in which Australians have been on active service, including the events leading up to, and the aftermath of, such wars and warlike operations". This intransigence has been a source of bitter division among directors, historians and archivists for decades. At times it has hinged on little more than semantic argument over whether the conflict was "war" (were the Aboriginal fighters guerrilla warriors?) and whether the locally raised militias, police and British military units qualified as an Australian defence force. Historian and former memorial deputy director Michael McKernan thinks so. Of the memorial's position that all this is the responsibility of the National Museum of Australia, he says: "It seems to me that is like saying that you've been put in charge of telling the story of Australia at war, but that that particular part of the story is too confronting or too uncomfortable – too hard, for whatever reason."

The identities of pitifully few of those held at Mitchell can be determined. The stories of most are lost, and Kanabygal, along with a few others, is an exception. The curators Pickering and Kaus have painstakingly trawled through the records that may accompany bones for clues.

There is plenty of evidence that some of the dead in question were frontier violence victims. Such as one man, whose head was sent to Edinburgh University in the early 1900s by Dr William Ramsay Smith, a Scottish-born doctor who moved to South Australia and became state coroner. The museum's file note reads: "The skull is clearly that of a murder victim, with a bullet entry wound in the back of the skull and an exit wound in the front. The path of the bullet suggests deliberate execution rather than defence. It is possible Ramsay Smith obtained the skull through local police… he was a man of suspect ethics who collected remains widely…"

Ramsay Smith was almost single-handedly responsible for what became Edinburgh University's vast collection of Indigenous Australian remains, all of which are now believed to have been returned. By some estimates, the former Edinburgh medical student took it upon himself to preserve in alcohol and dispatch the soft tissue and bones of up to 600 people to his friend, DJ Cunningham, professor of anatomy at Ramsay Smith's alma mater. The remains included tongues, skin, male genitals and organs, as well as full skeletons, skulls and limb bones.

Some of the remains invariably became part of private collections. Other European anatomy schools, and individual clinicians and anthropologists, sought out their own "specimens". There is anecdotal, though reliable, evidence of Australian pastoralists and amateur anthropologists procuring body parts for visiting European collectors. Some of the anthropologists, attracted to phrenology, asked for skulls, while others wanted skin with elaborate tribal markings. Medical schools, still under the spell of Darwinism, wanted full corpses and skeletons to compare with the Anglo Saxon dead, so they might reinforce the fallacious orthodoxy that each race represented a distinct evolutionary phase. Some Indigenous Australians may have been killed specifically on behalf of visiting Europeans.

It would appear that others were marked for dissection and dispatch to Britain even before they died. Wunamachoo, a Yawarrawarrka man who was found unfit to plead (he spoke no English) after an alleged tribal killing, died in Adelaide Asylum in 1903. Ramsay Smith defleshed his skeleton and sent the bones to Edinburgh, where they remained until the 1990s.

Poltpalingada, or Tommy Walker, a Ngarrindjeri man, was well known around Adelaide, where he lived on the streets in the late 19th century. When he died in 1901, the city's stock exchange paid for his funeral. But little of Poltpalingada was buried; Ramsay Smith dissected him and only a portion of soft tissue went into the coffin. His skeleton was sent to his friend in Edinburgh.

In 1903, revelations about Poltpalingada's fate sparked a public inquiry that revealed sordid details about the illicit trade in body parts (skeletons £10 apiece) that flourished in Ramsay Smith's morgue. Aboriginal bodies were in particular demand. A morgue assistant recounted stories of heads in kerosene tins. According to other witnesses, Ramsay Smith was also known to shoot corpses with a rifle, then study the wounds.

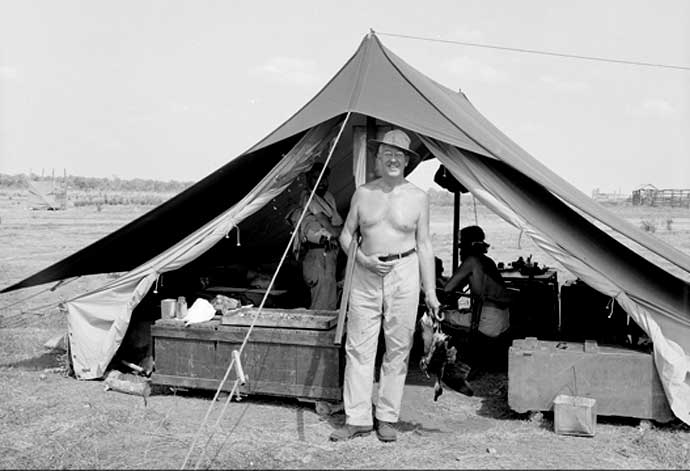

Frank Setzler at Gunbalanya (Oenpelli Mission) during the American Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land, 1948.

Setzler was the most senior of the four Smithsonian scientists who went to Arnhem Land, he served as deputy leader of the expedition. The gatherings from this expedition included scientific and anthropological reports and ethnological collections. The removal of human remains fell within this broader project of ethnological collections. This and many other similar expeditions were often known as the 'bone takers' or 'bone collectors'.

(Photographer unknown - National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution)

The case shocked polite Adelaide. But then Ramsay Smith, exonerated by the inquiry, resumed his duties. At his death in 1937, well over 100 human skulls were found in his home. Michael Pickering says the big unanswered question about Ramsay Smith was whether he was "body shopping". Pickering asks: "Were individuals selected and isolated until such time as they died from natural causes, and their remains became available? Was he doing this to keep favour with his old medical school?"

It would seem so. Eventually, a highly appreciative Cunningham helped Ramsay Smith to win membership of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and to become a Fellow of the Royal Anthropological Institute.

While the 18th- and 19th-century trade in body parts hinged largely on an export market (as well as on private collectors: stories abound of Aboriginal skulls adorning drawing room mantles in pastoral homesteads), in the 1900s Australian institutions were amassing very big collections, too. None more so than the Australian Institute of Anatomy, which began with a vast private collection of native fauna and Aboriginal artefacts belonging to a wealthy Melbourne orthopaedic surgeon, Dr Colin MacKenzie.

The institute's collection evolved eclectically, to incorporate items such as the racehorse Phar Lap's heart, while in 1935 the Hunterian Museum in London donated its "war wounds" (body parts, including limbs and torsos, of first world war personnel). Several private collectors, meanwhile, donated vast acquisitions of Aboriginal ethnographic material – secret and sacred objects, bark art, hunting weapons and Indigenous bones and body parts. Around this time, an amateur anthropologist called George Murray Black began ransacking sacred sites on MacKenzie's behalf. The National Museum of Australia, which later inherited the collection, addresses matter-of-factly this onerous truth at its heart: "For MacKenzie… there was a close link between the fate of Australian fauna and Aboriginal people. MacKenzie saw a parallel between the impact of settlement on wildlife and declining numbers of Indigenous people. As he described it, 'Thanks to poison and the gun they are rapidly following the fate of the Tasmanian nation which was completely destroyed in a period of about 40 years, constituting the most colossal crime our earth has known'."

By the early 1930s, MacKenzie's institute had acquired the bones and other body parts of thousands of Indigenous Australians. The vast collection, and its conflation of human and animal remains, is dramatically illustrated in a 1934 photograph, which depicts glass cases of hundreds of skulls, leg and arm bones; others hold full skeletons, adult and child. Dispersed among them are marsupials and birds.

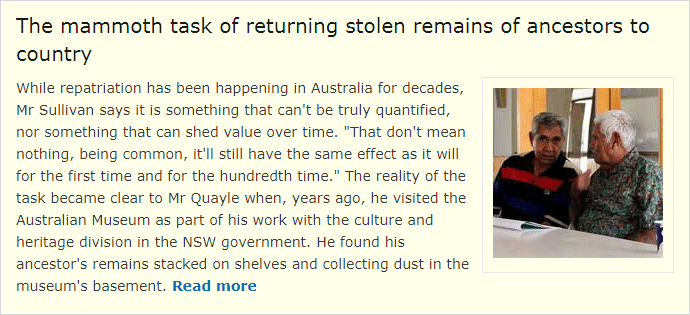

Chief law man Jacob Nayinggul during the ceremonial reburial of remains in Arnhem Land; the bones had been in the Smithsonian Institution in the US for more than 60 years.

Black collected for MacKenzie and, after MacKenzie's death in 1938, for his successor. He systematically ransacked Aboriginal burial grounds across at least two states. Between 1943 and 1950 alone, he collected the bones of 804 individuals, including 500 skulls, for the Anatomy Department of the University of Melbourne.

Black collected as many bones as he had crates to hold them. In 1940 he wrote to the Anatomy Institute: "I regret to say that through lack of cases I was unable to pack most of the specimens or to arrange for shipment… [I] packed 13 cases of skeletons and long bones leaving unpacked enough skeletons and long bones for about 12 cases… I dumped all the incomplete skeletons except long bones into the creek… as you appear to only require complete skeletons."

Black's motives are opaque. They exclude money; the institute did not pay him. He explained: "My donation of material to the Institute of Anatomy was made with the idea of it being of use to the scientists at the present time, as this material is fast being destroyed by erosion, rabbits and by measures taken to destroy the rabbit." There was no humanity in his reasoning, viewing, as he did, the dead Indigenous Australians purely as "material".

The past is not another country. I know that when I look around this room in Mitchell, at the cardboard boxes. And this is reinforced when Mike Pickering shows me the containers – a battered cigarette box, a Macfarlane Lang & Co biscuit tin – in which Aboriginal body parts that have lain around in private collections in Australia for generations are being sent to the museum. Some are returned anonymously. Others are brought in by family members who have discovered them in the dusty corners and keep-sake cabinets of old homesteads or from deceased estates. And I know the past is intrinsically linked to the present when I go into the State Library of Queensland to read the reminiscences of Korah Halcomb Wills. Written towards the end of his life in England, where he was born, there is no hint of the monster in the curlicues of a neat, cursive hand. The diary exudes confession under compulsion – of imminent death, the fear of retribution in the afterlife, perhaps – but there is nothing of genuine atonement in it.

Wills migrated to Adelaide, then moved to gold rush Victoria in the 1850s, where he worked as a butcher, before moving to Queensland in the 1860s. A successful hotelier in Townsville and Bowen, as well as Bowen mayor, Wills recounts how the police superintendent would seek men of "pluck and a quiet tongue" to help disperse the Aboriginal people who threatened and attacked settlers: "You may bet we weren't backward in doing what we were ordered to do and what our forefathers have done to keep possession of the soil that was laying to waste and no good being done with it, when… our own white people were crying out for room to stretch our legs on."

He recounts joining a reprisal party in the mid-1860s, while mayor, for the killers of a shepherd: "They got on top of a big mound & defied us & smacked their buttocks at us & hurled large stones down on us, & hid themselves behind large trees and huge rocks but some of them paid dearly for their bravado. They had no idea that we could reach them to a dead certainty at the distance of a mile… and out of one of these mobs of Blacks I selected a little girl with the intention of civilising."

Holding the child captive, Wills writes, "I took it on my head to get a few specimens of certain Limbs, and head of a Black fellow, which was not a very delicate occupation… I took my trophies home to the Station that morning, and in the afternoon I took some of my limbs to the Lagoon also to divest of its flesh as much as I could… I packed them home to Bowen as well as my little protegee of a girl let me who rode on the front of my saddle for over 80 mile and crying nearly all the way. And as I neared the town of Bowen I met different people who hailed me with how do, and so on and where did you get that intelligent little nigger from. My answer was that I had picked her up in the bush lost to her own tribe and crying her heart out… I decided to take her home and bring her up with my own children which I did, and even sent her to school with my own." He expresses regret at the child's subsequent death, though dwells on it less than he does on the death of a favourite horse. I was wearing white cotton gloves while leafing through Wills' manuscript – standard practice when handling such old archival paper. Intermittently I was compelled to peel the gloves off and head for the bathroom to wash my hands.

Many Indigenous remains are still in private or institutional collections, including Australian state museums from where they, too, are slowly being repatriated. Others are in the vast collection at Mitchell, awaiting return to country. The Australian government–appointed Advisory Committee for Indigenous Repatriation has recommended that a "national keeping place" be built in Canberra for Indigenous remains that cannot be returned. Last year, Yawuru elder and National Museum council member Peter Yu told me, "It would become like a beacon of conscience, where it reminds us of the importance of history and what we can do to each other, but where we can learn from what we've done to each other. One of the problems with Australia is that we don't really recognise the true history of the country. It was a brutal history."

Shane Mortimer – the most senior elder of the *Ngambri people, and the great-great-great-great-grandson of OnYong, whose skull became a sugar bowl – says the keeping place should be built where the Aboriginal Embassy stands today. "It should be a place to which Aboriginal people come to match DNA with the remains that are currently held at the national museum and elsewhere," he says. It should also be a place where Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians can come to commemorate those who died in the frontier war, because the war memorial absolutely refuses to tell that story." Mortimer recently made his recommendation to the government; it has yet to respond.

The same week the advisory committee recommended an Indigenous keeping place to government, Abbott announced his desire for an Arlington-style cemetery for Australian war dead and dignitaries. Meanwhile, the remains of 725 men, women and children remain in limbo out at Mitchell, stored in cardboard boxes.

Originally an edited extract of an article that first appeared in 'Meanjin' by Paul Daley from the 'Guardian' on 14 June 2014 (Further editing by Sovereign Union in April 2015 and August 2016)

* According to Josephine Flood's research Ongyong was a Ngunnawal warrior, not 'Ngambri'. SU has also been advised that there is a dispute on the validity of Ngambri tribe.