Murrawarri claim renews sovereignty campaign

Greg Dyett and Jeremy Geia SBS Podcasts 09 April 2013

A declaration of independence refreshes the campaign for Indigenous sovereignty over parts of Australia.

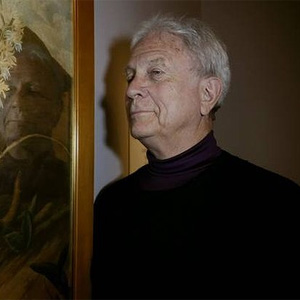

Veteran Aboriginal activist Geoff Clark says he's encouraged by what he calls a reinvigoration of the campaign for Aboriginal sovereignty in Australia.

His comments came as the Murrawarri people from northern New South Wales declared their independence.

The Murrawarri say they're now a republic with their own constitution and bill of rights and they've given Queen Elizabeth II 28 days to respond to their declaration.

Greg Dyett reports.

The Murrawarri say they never ceded their sovereignty or ultimate title over their ancient homeland and never gave permission for the colonisers to enter their land.

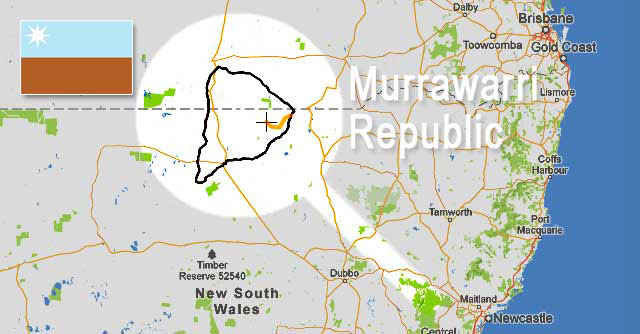

It's an area known as the Culgoa River region, which includes towns like Bourke and Brewarrina in northwest New South Wales and Cunnamulla in southeast Queensland.

Fred Hooper is from the Murrawarri Peoples Council of the Murrawarri Republic.

"We firmly believe that our ultimate title has not been taken away by the King of England when Captain Cook first placed the flag on Possession Island. We believe that at that time the Murrawarri nation was an independent Murrawarri nation with boundaries and with the boundary that we've re-drawn up which had laws and customs that governed our people and governed our country and governed our land."

To press their case, Mr Hooper says they've written to Queen Elizabeth II asking her to produce any documents which might suggest otherwise.

"If she can't provide this documentation within 28 days then what we would do is that we consider that the Murrawarri Republic is, I suppose, an independent nation in the world and we'd be seeking United Nations assistance in being recognised and we'd certainly be seeking other countries' recognition of our independence as well."

That deadline expires at the end of April.

Former head of the now-defunct Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission Geoff Clark says the case being made by the Murrawarri people is ambitious but he's pleased it's being advanced.

"I think you have got to applaud the Aboriginal groups which may seem, you know, a little bit far-fetched to state that you want a sovereign state within Australia but unless you have the idea, the dream, the aspiration, all you're subjected to is the dilution of the status quo on our current situation."

Michael Anderson describes himself as the coordinator of the Sovereign Union Government and he says Australia - and the world - have to take this claim seriously.

"There are several international conventions, together with a number of resolutions at the General Assembly of the United Nations, that call upon the internal decolonisation of countries, and Australia has failed to do that. And of course the British secured the legislative authority of the Australian state, but we've got to remember the Australian state sits on top of a land and the land is being contested by many nations."

Over the past 20 years, arguably, the main dialogue between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders and their non-Indigenous counterparts has focused on reconciliation.

To that end, Kevin Rudd's 2008 apology to Stolen Generations is considered by some to have been a watershed.

More recently the debate has shifted to constitutional recognition for Aboriginal people, which some support.

However others, such as Geoff Clark, have long argued that incorporation into the constitution would weaken the campaign by those who argue for Aboriginal sovereignty.

"Being included in the Constitution is to be consumed by the nation state and that's never been what Aboriginal people on my side of politics have advocated. We've advocated that we're nations of people prior to the colonisation process and there's never been a proper instrument or a proper process whereby we recognise what elements of that sovereignty or native sovereignty would still exist, what elements could be enacted or recognised that would support Aboriginal people. On the other side of that coin, what elements would there be to support industry, for instance, like mining?"

Mr Clark says the Murrawarri case, like others that have gone before it, is ambitious but deserves proper consideration.

"The aspirations you have to applaud because stemming from that aspiration would be coordination, customary consideration of law and social behaviour, so there would be lots of positive elements that could be drawn from people wanting to assert their rights to want to govern themselves, to want to be responsible for that governance, to carry out an economy. If you're going to talk about statehood you'd have to talk about laws, you'd have to talk about running an economy, running a government or parliament. These are fine aspirations for any group of people and should not be seen as a threatening element."

Eminent historian Professor Henry Reynolds says the issue of Aboriginal sovereignty has never been decided by Australian courts because in previous claims the courts have determined that they're not equipped to make a ruling.

The courts' position rests on the view that as they're the products of the sovereignty claim, they can't make decisions beyond the claim or behind it.

The result, he says, is that there's no understandable way in which the loss of Aboriginal sovereignty can be explained in Australian law.

Professor Reynolds says most Australians would accept the Aboriginal peoples did have sovereignty before the British arrived under standard definitions of sovereignty.

"In law, the only way in which sovereignty can be lost is either by conquest - that is, it's taken by force - or by treaty, by session, which happened in New Zealand with the Treaty of Waitangi. Now, in Australian law, we don't say Australia was conquered, we simply avoid that idea and there have certainly never been any treaties. So there is this fundamental problem. Where any Aboriginal group approaching this problem does need to do, and it seems as though this is maybe the way they are approaching it, is to ask for the Australian courts to show when and how they lost their sovereignty and I think that's a problem which simply has to be dealt with by the Australian courts."

Beyond that, Professor Reynolds says either the Australian government itself or one of the larger human rights organisations could ask for an opinion from the International Court of Justice as well as make appeals to the United Nations.

But he says the issue should really be dealt with by the High Court.

"I mean it only took Eddie Mabo and two other Murri Islanders to overturn 200 years of law regarding property. (High Court's Mabo decision) It doesn't take a large number to go to the courts. I can't see it happening politically for a long time but the courts eventually may feel they have to deal with it. In a way, what they're saying is that we, the highest court in Australia, can't make a decision about a fundamental legal issue and that seems to be a strangely colonial attitude to have towards the problem and I think eventually it's to be expected that Aboriginal people will want to know, have it explained to them, how and when they lost their sovereignty and whether there are some people who have remnant sovereignty left."