Jail rate for First Nations children is soaring at an alarming rate

Figures show that the number of First Nations children being jailed is rising enormously, as the tide of social dysfunction in urban and regional centres has never been properly addressed.

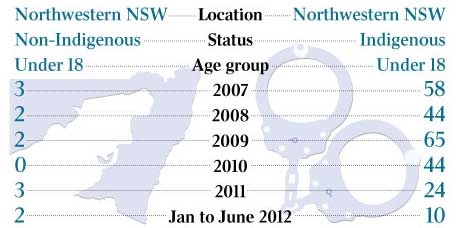

More than 250 indigenous youth in northwestern New South Wales have been sentenced to juvenile prison terms during the past five years compared with only 12 non-Aboriginal children, the Australian newspaper reported.

Figures from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare show the national rate of Aboriginal juvenile incarceration has risen to 31 times the non-indigenous rate and rising.

Figures from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare show the national rate of Aboriginal juvenile incarceration has risen to 31 times the non-indigenous rate, up from 27 times in 2008.

The figures come amid concerns that juvenile jails have become storing houses of Aboriginal children often growing up in squalor and despair.

Dubbo police inspector Rod Blackman told the newspaper that many Aboriginal children viewed detention centres as safehouses where they get three meals a day and a roof over their heads.

He said the system wasn't working as there was no deterrent factor and detention centres offered no real prospects of rehabilitation.

Number of persons who received a penalty of inprisonment or control order

for their principal offence

Black sentences soar as juvenile jails become a 'storing house'

Natasha Robinson The Australian 5 January 2013

The number of Aboriginal children being jailed is soaring at an alarming rate as the criminal justice system struggles to contain a rising tide of social dysfunction in urban and regional centres.

Amid concerns that juvenile jails have become storing houses of Aboriginal children growing up in squalor and despair, it has emerged that more than 250 indigenous youth in northwestern NSW have been sentenced to juvenile prison terms during the past five years compared with only 12 non-Aboriginal children.

Incarceration rates of Aboriginal children are also worsening in other states, as is the chasm between the numbers of indigenous and non-indigenous children in juvenile detention centres.

Figures from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare show the national rate of Aboriginal juvenile incarceration has risen to a startling rate of 31 times the non-indigenous rate, up from 27 times in 2008.

In 1994, young Aboriginal people were 17 times more likely than non-Aboriginal juveniles to be incarcerated.

There is also concern that the constant treadmill of child re-offending among indigenous youth appears to be driving errant sentencing patterns in western NSW children's courts, where The Weekend Australian has identified a number of cases in which Aboriginal boys received the harshest sentences for stealing ever recorded by juveniles in NSW.

The legal system's handling of the problem has also prompted frustration within police ranks, with a senior officer based in the city of Dubbo arguing that juvenile detention centres offer no real prospects of rehabilitation, and perversely, many young Aborigines see them as safehouses because they get three meals a day and a roof over their head.

While disputing allegations of overpolicing of Aboriginal youth, Dubbo police inspector Rod Blackman, the Orana local area crime command manager, has issued an urgent call for alternatives to the criminal justice spiral that is seeing greater and greater numbers of Aboriginal children sent to juvenile jails.

He said that jails were operating as safehouses for vulnerable children and the criminal justice system was becoming a proxy social service provider.

"As controversial as it may sound, sadly there is this very small portion within our communities that you can almost predict that today's babies are tomorrow's offenders," Inspector Blackman said.

"As a society, I think that's a terrible thing, that we can stand back and say, 'Well, we've now got two, three, four generations of the same conduct and the same sort of dysfunction within the same household', and yet these kids are going to be brought up in the exact same manner.

"I've lost count of the number of children who when they are finally refused bail and end up in our juvenile detention centre, are quite happy because they know they're going to get fed three times a day, and they know they're in a safe environment, and quite often they've got other family members in there.

"There is no deterrent factor.

"The current system is not working."

The number of Aboriginal children being sentenced to juvenile detention in NSW is largest in the state's northwest, which includes the council shires of Dubbo, Bourke, Brewarrina and Walgett, the mid-north coast, northern NSW and the Hunter region.

Nationally, the Northern Territory and Western Australia stand out as having by far the largest proportion of Aboriginal young people in prison, with very few non-Aboriginal children in juvenile detention at all in the NT. Indigenous children make up 70 per cent of the juvenile prison population in Western Australia.

The Aboriginal Legal Service NSW/ACT points to overpolicing of Aboriginal youth and the misuse of the juvenile detention system by magistrates in rural areas with large Aboriginal populations as significant contributors to the overrepresentation of indigenous youth in children's courts.

"The causes of the horrendous rate of Aboriginal juvenile overrepresentation are complex but in the rural and remote parts of the state, sustained and targeted policing and draconian sentencing trends are playing an undeniable role," said Stephen Lawrence, principal solicitor with the ALS western zone.

"Certain magistrates are regularly imposing extraordinarily harsh sentences on Aboriginal youth that simply cannot be justified under state sentencing law."

According to figures obtained by the ALS and seen by The Weekend Australian, the maximum number of non-Aboriginal children from Dubbo and surrounding areas being sentenced to detention in any year during the past five years is three, whereas in some years more than 60 Aboriginal have been sentenced to terms of incarceration.

There is strong pressure from within communities in the NSW northwest and central west for magistrates to take repeat offenders, who are overwhelmingly Aboriginal, off the streets, but some members of the Dubbo indigenous community complain that Aboriginal children are actively and unfairly targeted by police.

They say police know who their targets are and rigorously monitor wayward boys using suspect target management plans, under which those on police watch lists are watched and "engaged".

In the past year, two Aboriginal boys were sentenced to as long as 18 months in juvenile jails for stealing $750 - court orders that exceeded the maximum sentence laid out under the law. One of the sentences was subsequently reduced. One of the boys was also given a 12-month juvenile jail term for possessing 1.8gm of marijuana and a third was given a 12-month sentence for stealing $70 worth of hamburger rolls, which was reduced to a good behaviour bond with no conviction.

The ALS alleges that magistrates sitting in numerous courts across the central and far NSW west are "sentencing in a radically harsh way".

"It used to be that social deprivation was a mitigating factor in sentencing. However, this increasingly doesn't seem to be the case. The tragedy of this utterly misguided approach is that nothing increases a child's prospects of moving on to a life of crime more than a stint in juvenile detention," Mr Lawrence said.

The idea that Aboriginal children are punished more harshly than non-Aboriginal children by the justice system is hotly contested by police, the judiciary and some academics.

In recent months, Dubbo magistrate Andrew Eckhold has been voicing his deep frustration from the bench at the inability of juvenile justice services and the court system to prevent repeat offending by children.

Children as young as 10 are appearing in court with extensive records and evidence of scant parental supervision. "I really don't know what our society can do about these matters," Mr Eckhold said during a case involving a 10-year-old boy facing multiple breaches of bail curfew.