Research suggests First Peoples were firestick farming in North Queensland for up to 140,000 years

"One reason we went off-shore in the first place was because the pollen record can be reliably dated," Dr Kershaw said.

Western scientific hyper theories put forward tell us the First peoples were on this continent 40,000 years ago, then 60,000 years, now 80,000 years, and they keep adjusting their story to keep up with their recent findings, but the work of Dr Peter Kershaw's palynology (the study of fossil pollen) research suggests that the first peoples were on the continent as long ago as 140,000 years ago.

Dr Peter Kershaw 'Forest fires illuminate the past'

Published in the Monash University publication 'Montage' 1992

Specks of prehistoric pollen and charcoal embedded in the ocean floor off the Great Barrier Reef may rewrite Australia's prehistory.

The surprise discovery of an abrupt change in the fossil pollen record around 140,000 years ago has probably pushed back the time of human colonisation of Australia by as much as 80,000 years.

Dr Peter Kershaw

(Monash University, Melbourne)

Dr Peter Kershaw, of the Department of Geography and Environmental Science, believes he has found signs of human disturbance in rainforest pollen patterns in a drill core from the edge of the continental shelf, 80 kilometres east of Cairns.

These signs are the mark of fire on the landscape. Dr Kershaw, one of Australia's leading experts in palynology (the study of fossil pollen) says the environmental changes are evidence that humans were deliberately firing the rainforest.

If he is correct, the known period of human habitation of the Australasian landmass would be more than doubled. The earliest radiocarbon dating of an Aboriginal site in mainland Australia is 40,000 years old. Using thermoluminescence dating, a Kakadu site has been dated between 55 and 60,000 years.

The core, which covers the past 1.5 million years, indicates that around 140,000 years ago a drier type of tropical rainforest in north-east Queensland, dominated by fire sensitive conifers, was subjected to a sustained increase in fire frequency.

Until then Australia's northern rainforests had slumbered in a virtually unchanging season cycle for more than a million years. But around 140,000 years ago the fossil pollen record shows a pronounced and durable shift.

Importantly, Dr Kershaw says the observed patterns of change in fossil pollen, fern spores and charcoal in the drill core cannot easily be explained by climate change. "There is no indication from the global record that the pattern of climate change with the past 150,000 years was any different from that of the preceding 500.000 years, he said.

An analysis of the core shows that at some time between 150,000 and 100,000 years ago there was a dramatic decline in Araucanian conifers like hoop pine and bunya pine, that had dominated extensive drier rainforests within the region. Today, these species are limited to small pockets of rainforest within north-eastern Australia.

"The change corresponds with increases in charcoal particles and eucalypt pollen," Dr Kershaw said. "This suggests that increased burning caused the replacement of the drier rainforests by open woodlands."

Later Aborigines are known to have used fire to create such habitats, suited to their preferred game species — kangaroos and wallabies. Dr Kershaw, who believes that the first forest fires were probably accidental, speculates that this practice could have evolved over time. "You don't have to do much to Australia to set it alight," Dr Kershaw said.

The drill core also shows at the same time a pronounced in-crease in mangrove pollen, consistent with large volumes of sediment being swept down from the coastal ranges as they were exposed to erosion. These sediments would have created a favourable environment for the expansion of coastal mangroves.

Dr Kershaw says the increase in charcoal and decline of conifer pollen most likely began around the height of an ice age 140,000 years ago. Ice ages produce drier climates, which would tend to increase the frequency of fire, but they also cause a dramatic drop in global sea levels," he said.

"Falling sea levels would have exposed land bridges by which early humans in southeast Asia could have reached Australia by crossing only a few, relatively narrow deep water gaps between Indonesia and the Australia-New Guinea land mass.

"Really, there is no evidence in any other continent of this type of sustained environmental transition as response to climate. The Australian record is unique.

"I think it's all fitting together. And the fact that these changes start down on the coast fits in with ideas about Australia being colonised first along its coastal regions."

Two decades ago, the late Australian National University palaeoecologist Dr Gurdip Singh argued that a transition from fire-sensitive to fire-tolerant vegetation 130,000 years around Lake George, near Canberra, was also caused by humans.

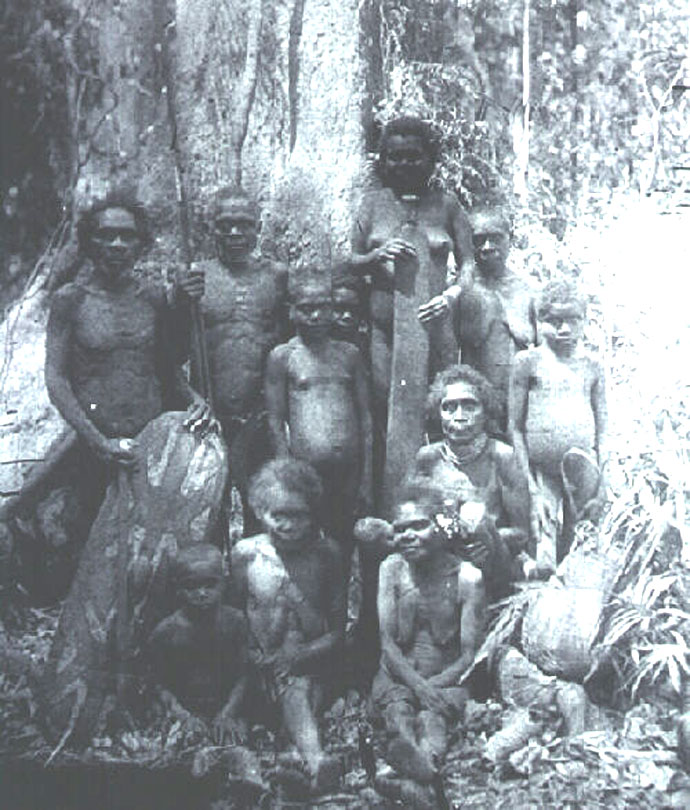

(Photograph courtesy of the Cairns Historical Society.)

He believed that a pronounced increase in charcoal in sediments from Lake George, accompanied by the replacement of a casuarina-dominated forest by eucalypt forest, resulted from humans firing the forest to create habitat suited to preferred game species, such as kangaroos and wallabies.

His theory was greeted with scepticism, in the absence of any archaeological evidence that humans had been in Australia any longer than about 30,000 years. But in the two decades since then, radiocarbon dating has extended the threshold for human colonisation of Australia back to at least 40,000 years in mainland Australia, and 36,000 for Tasmania.

Some prehistorians believe these radiocarbon dates substantially underestimate the true age of such sites, because they are at the limit of resolution for the technique: even slight contamination by younger carbon can make samples appear thousands of years younger than they really are.

Because carbon dating can be very unreliable beyond about 35,000 years, prehistorians have lacked a way to date Australian sites that, on the evidence of their geological setting, appear to be considerably older.

Using a new application of a new technique called thermoluminescence dating, Australian National University prehistorian Dr Rhys Jones has derived a tentative age of 55 to 60,000 years for human habitation of a rock shelter in Kakadu National Park.

Many prehistorians now accept Dr Kershaw's evidence that a similar change from fire-sensitive rainforest to eucalypt forest which began about 38,000 years ago around Lynch 's Crater, on the Atherton Tableland inland from Cairns, was caused by humans deliberately firing conifer dominated rainforest.

The much earlier date from the offshore core implies that the change may have taken place gradually. The sample resolution of the core is too coarse to determine the rate of change in coastal environments but it is possible that it occurred over many thousands of years.

The evidence from the more detailed Lynch's Crater record certainly indicates that the replacement of araucarian forest by eucalypt woodland around the site took a long time, about 120,000 years. Why this occurred much later than on the coast could be explained partly by initial inhabitation of coastal areas.

This fits in with many archaeologists' ideas of coastal colonisation. The transition may also have been slowed by the prevalence of generally wet interglacial conditions between about 130,000 and 80,000 years ago.

Dr Kershaw says that the vegetation changed and stabilised in new assemblages, distinctly different from those that had preceded them.

"The original vegetation patterns never returned, and the rainforests of north-eastern Queensland have seen no change of comparable magnitude in the past 100,000 years," he said.

The fossil pollen types and fern spores in the drill core represent only a small, skewed sample of the full spectrum of species that grew in the tropical rainforest. However, once these biases are understood, it is possible to infer the composition of the prehistoric rainforests in which these conifers and ferns grew, using modern assemblages as a guide.

Dr Kershaw says that most rainforest flowering plants are pollinated by animals or insects and tend to have limited dispersal ability. Conifers and ferns, which have wind-blown or waterborne pollen or spores, are over-represented in the drill core because they disperse more widely, finding their way into rivers and streams that drain into the coastal waters of the area.

The drill core, obtained last year by the international Ocean Drilling Program, was analysed by Dr Kershaw and Dr Merna McKenzie, of the Centre for Palynology and Paleoecology, in collaboration with Dr Andrew McMinn of the Institute of Antarctic and Southern Ocean Studies, University of Tasmania.

Mr Frank Peerdeman of the Research School of Earth Sciences at the Australian National University, Canberra, provided age control by tying changes in the composition of marine organisms in the core with the well documented global marine stratigraphy.

"One reason we went off-shore in the first place was because the pollen record can be reliably dated," Dr Kershaw said.