The Simple Case For Greater Aboriginal Heritage Protection

Proposed changes to the West Australian Aboriginal Heritage Act will not provide greater protections, writes Nick Herriman.

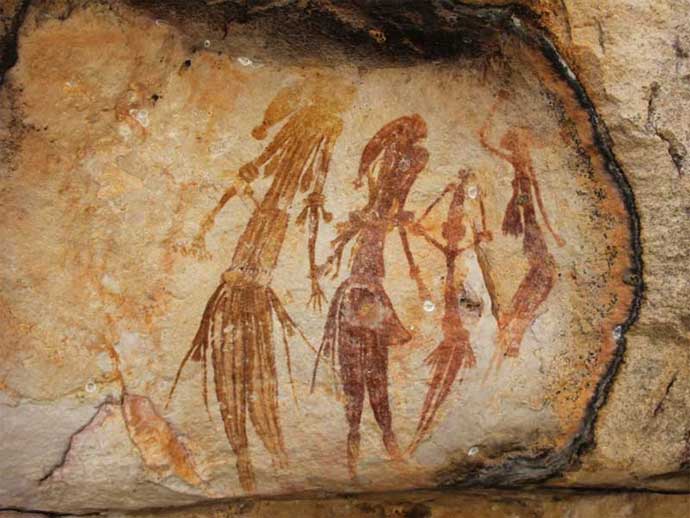

Wandjina figures are some of the most visually striking of all images. The Worrorra, Wunambal, and Ngarinyin people of the north-western and central Kimberley say that the Wandjina are the creator beings of the Dreaming, and that they made their world and all that it contains. They are found in many rock art/culture sites in caves and rock shelters throughout the Kimberley. Wandjina are usually painted as full-length, or head and shoulder, figures, either standing or lying horizontally. Their large mouthless faces feature enormous black eyes flanking a beak-like nose. The head is usually surrounded by a band with outward radiating lines. Elaborate head-dresses are both the hair of the Wandjinas and clouds. Long lines coming out from the hair are the feathers which Wandjinas wore and the lightning which they control.

Nicholas Herriman www.newmatilda.com 21 July 2014

Many Australians see development, including mining, to be important for the economy and our well-being.

At the same time, we recognise this needs to be done in an environmentally and socially responsible way. Certain laws have been created to ensure this.

However, a Western Australian law intended to maintain social responsibility is in grievous danger. This is because WA's parliament plans to revise legislation designed to protect Aboriginal heritage.

The revisions will make it easier for developers to disturb this heritage. We have to take a step back tens of thousands of years to see why.

As with other parts of Australia, all of Western Australia's mainland was once, or still is, inhabited by Aboriginal Australians.

In some locations, Aboriginal people have been violently dispossessed of land. In others dislocation has been less sudden. But what do all these places hold in common?

We can be sure that the land on which our homes sit - urban centres, farming and mining areas, even the remotest outback - has at some time been used by Aboriginal people or their descendants in customary and traditional ways.

Evidence of this can take material or tangible forms such as shields, spears, bones.

Evidence can also be abstract or intangible; such as stories and rituals.

Either way, such places or objects, where they still exist and can be identified, can be said to have Aboriginal heritage.

This can include anything from places where stone tools were made, to cave and rock paintings, to places where the ancestors created or altered the landscape.

The Bradshaw figures rock art/cultural symbols are found in the north-west Kimberley region of Western Australia. The identity of who painted these figures and the age of the art is a contentious theme in archaeology and amongst Australian rock art researchers, and has been since they were first discovered and recorded by pastoralist Joseph Bradshaw in 1891 after whom they were named. As Kimberley is home to various Aboriginal language groups, the rock art is referred to and known by many different Aboriginal names, the most common of which are Gwion Gwion or Giro Giro. The art consists primarily of human figures ornamented with accessories such as bags, tassels and headdresses.

The fast pace of development in Western Australia has destroyed much Aboriginal heritage. In recognition of this, WA's parliament passed, in 1972, the Aboriginal Heritage Act.

The Aboriginal Heritage Act intended to protect Aboriginal heritage by making it illegal to disturb places and objects of traditional use and value.

The idea was that developers, whether drilling for nickel in the Goldfields or subdividing in the suburbs, could disturb an Aboriginal heritage site or object. And this would be illegal.

There are good aspects to the law as it stands. For example, if developers wish to work on a heritage site, they can negotiate with local Aboriginal people.

Moreover, as many developers take social responsibility seriously, they are prepared to sit down and work through these issues.

However, if things go bad, the law is not particularly onerous. After four decades, you could count the number of actual prosecutions on your fingers.

And, unusually, ignorance is a defence: the law states "… it is a defence for the person charged to prove that he did not know and could not reasonably be expected to have known" that he destroyed heritage. But these are comparatively minor issues.

A major ‘loophole' plagues the current legislation. To provide a simple example, currently, if a developer wants to disrupt a site associated with the Dreamtime, the developer can request that the Minister whose portfolio includes Aboriginal affairs allows it.

The Minister almost always does allow such disruptions. Granted, there is a committee to look at these requests, but it only advises the Minister and makes no binding decisions.

Furthermore, there is no hearing or court. The Aboriginal people who maintain their heritage is under threat have no formal means to present their case to the Minister.

The Minister is not accountable for the decision made, nor is there any transparency; the rationale for the Minister's decision does not need to be made public. The law appears to deprive Aboriginal people of natural justice.

There is a sense from both developers and Aboriginal people that the current law needs revision.

Developers want clearer timeframes and rationales in negotiations with Aboriginal people.

Aboriginal people want to be formally heard, if not have a say, in the Minister's decisions about their heritage.

Murujuga, usually known as the Burrup Peninsula, is a peninsula in the Pilbara region of Western Australia, adjoining the Dampier Archipelago and near the town of Dampier. (The region is sometimes confused with the Dampier Peninsula, 800 km to the north-east.) In Ngayarda languages, including that of the indigenous people of the peninsula, the Jaburara people, murujuga means "hip bone sticking out". The peninsula is a unique ecological and archaeological area since it contains the world's largest and most important collection of petroglyphs – ancient Aboriginal rock carvings some claim to date back as far as the last ice age about 10,000 years ago.

So when a revision to WA's Aboriginal Heritage Act was announced, many were excited. The anticipated draft can be downloaded here.

One positive is that proposed punishments have been increased for disrupting Aboriginal heritage from a maximum of $20,000 and imprisonment for nine months to $100,000 and 12 months imprisonment. But as prosecutions are so rare, this is likely to have minimal effect.

On the other hand, a quick look demonstrates why so many are disappointed with the proposed revision to the law. Sections 17 and 18 of the draft law are crucial.

If a developer wishes to develop a certain plot of land, the draft proposes to allow the Minister handling Aboriginal issues to say, in the developer's interests, that there is no heritage, or that there is heritage but development may take place.

In such a scenario there seems to be little (possibly Section 19D(1)(c)) or no recourse if local Aboriginal people, or anyone for that matter, disagrees with the decision.

On the other hand, if the Minister declares that there is heritage in a particular site, the proposed law provides ample room for developers to challenge this.

Instead of limiting, the current revision seems to empower the Minister. Developers are also provided with greater rights to challenge decisions adverse to development.

This means the revised Act makes it easier for a developer to disrupt heritage if one was so inclined.

However, the role of Aboriginal people in advising, challenging, or making accountable the CEO's decisions remains limited.

As stated, a revision to the law would be welcomed by both developers and Aboriginal people.

However, it would be hoped that at the very least, traditional owners of the land should have more say in the process.

Without this, it is possible, if not likely, that much more Aboriginal heritage in Western Australia could be legally damaged or destroyed.

Mining and development can be a great thing, but it does not need to be done at the expense of Aboriginal culture.

* Dr Nick Herriman is a lecturer with the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the School of Social Sciences and Communications at La Trobe University.