Many First Nation Groups lived in villages, farmed and traded

FORMALLY CONSIDERED FOR UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE

This 6,600-year-old, highly sophisticated aquaculture system developed by the Gunditjmara people will be formally considered for a place on the Unesco world heritage list and, if successful, would become the first Australian site listed exclusively for its Aboriginal cultural value. Article The Guardian

.

Artist impression of hut: ABC Catalist

Traditional stone house site: Budj Bim Tours

Eel trap: Budj Bim Tours

Graham Phillips The Age March 13 2003

Evidence shows First Nations peoples lived in villages and farmed fish 8000 years ago.

According to Heather Builth, Australian Aborigines were not nomads, they lived in villages. This conclusion, which contradicts the long-held belief that Aborigines existed solely as wandering hunter-gatherers, is a result of research carried out by the Flinders University researcher over the past eight years.

She says the Gunditjmara in the Lake Condah region of western Victoria were also farmers and that they modified more than 100 square kilometres of the landscape to breed eels. They constructed artificial ponds across the grassy wetlands and dug channels to connect them. And the whole scheme was systematically punctuated with eel traps.

"The area was naturally a wetland, with natural swamps, but they modified these with weirs, channels and dams to make the whole landscape eel-friendly," says Builth.

Some of the modifications were impressive. In parts, the channels were dug through rock to allow water to flow from swamp to swamp. Some of the chains of channels and ponds stretched more than 30 kilometres.

But Builth's research revealed something more remarkable. She estimated the output from these eel farms could have fed up to 10,000 people. On the basis of this research, she believed this was more an ancient fishing industry than a subsistence farm, and she set out to prove it.

Bruce Pascoe 'Dark Emu' Author

She had noticed the landscape was scattered with burnt, hollowed out trees that were often next to the eel traps. Could the structures have been ancient smokehouses? Smouldering fires could have been lit in the bases of the trees and the freshly caught eels hung up above, to be preserved by the smoke.

To confirm the theory, Builth took soil samples from the bases of four trees. Laboratory analysis revealed that the samples did contain traces of eel fat.

"Suddenly the whole picture changed. The Gunditjmara weren't just catching eels, their whole society was based around eels. And that to me was the proof," she says. The villages associated with the Lake Condah fish farm, she says, were actually more like company towns, with dwellings built to house the people who worked the farms. "It's like you have your council houses for the factory. That's what was going on here," says Builth.

Archaeologists know a society undergoes a quantum leap in sophistication when it can produce a surplus of food, because the community has more time to devote to pursuits other than basic survival.

"This puts the people here in a different category than we've generally put Aboriginal groups."

Aborigines are usually thought of as living in small communal bands, where power and wealth are shared relatively equally. But Builth believes the Lake Condah farmers lived in a much more complex society.

"I think what we had here was a hierarchical, structured society. We had chiefs, for example, with lots and lots of power."

Perhaps the biggest surprise about the Gunditjmara prehistoric fishing society came when Heather asked Monash University geologist Peter Kershaw to try to put a date on it. He drilled into some of the ponds that still have water today (much of the area was drained in the 1800s) to take cores of soil from the muddy bottom. Kershaw was able to drill 13 metres before hitting the bedrock, which produced a core that stretched all the way from the present day down to soil made 18,000 years ago.

Like a forensic scientist, Kershaw hoped to date the eel farm from indirect evidence. Eventually he found the region of the core where the plant species abruptly changed. The vegetation had gone from being dominated by plants that preferred a drier environment, to water-loving aquatic species.

"This doesn't occur naturally," says Kershaw. "It had to have some help. People have been here - that is the most likely explanation. And those people could well have been human eel farmers flooding the area with an artificial ponding system."

But the most dramatic finding was when Kershaw radiocarbon-dated the part of the core showing the abrupt change. It was 8000 years old, making the fish farming industry at Lake Condah one of the most ancient.

The only comparable group at this early time were the indigenous people on America's north-west coast, who caught salmon as they naturally migrated up the rivers. But the Gunditjmara's farming practices were far more developed. They actually brought the young eels in from the ocean and trapped them in their artificial waterways for up to 20 years.

Builth also suspects the Gunditjmara traded the smoked eels across Victoria and South Australia. The famous escaped convict William Buckley, who lived with Aborigines for many years, mentioned eels from western Victoria in his diaries, and so did Victoria's first protector of Aborigines, George Augustus Robinson.

Builth was originally attracted to Lake Condah because of the boulders scattered all over the ground. Many of them seemed clumped into circular patterns. Since the 1970s, people had argued these were the remains of the village huts' stony foundations. But the claims had always been controversial.

Lake Condah, Victoria - where the remains of a complex society existed before the illegal European invasion

In 1990, the Lake Condah stone circles were officially surveyed, and the conclusion - after just a 40-day study - was that most of the circles were not hut foundations at all.

This was too much for Builth and she began her Lake Condah research. The research eventually ended with a highly praised PhD thesis that demolished the Victorian Archaeological Survey's negative conclusions.

To prove that the circles of stones were not natural formations, Builth painstakingly measured and weighed each of the rocks in them. She then performed a statistical analysis and showed that the chance of their coming together in this way naturally was almost zero. The only likely remaining explanation was that the circles were the stone foundations of huts.

So how could previous archaeologists have missed all this, given the scale of the operation and that the fish farms would still have been operating when Europeans arrived?

Builth suspects it is because the Gunditjmara disappeared quickly after white settlers came. "History tells us, many (of the settlers) had a military background and they knew tactics - they knew how to survive - they knew how to win, and they knew how to get rid of Aboriginal people pretty quickly."

By the time archaeologists had arrived in Australia the only Aboriginal people still leading traditional lifestyles in significant numbers were the ones living on the less desirable land.

"Most studies - certainly anthropological studies - focused on people dwelling in desert in semi-arid conditions, because they were the last people to live in their traditional land. These people (the Gunditjmara) were the first to lose their land, that's the difference."

The Kerrup Gunditj clan at Lake Condah had traditionally engineered an extensive aquaculture system at Lake Condah. Other Gunditjmara clans along the Budj Bim landscape worked together to establish kooyang (eel) trapping and farming systems, developing smoking techniques to preserve their harvest - probably one of the first cultures in the world to do so.

Remains of a village at Lake Condah

Lake Condah Indigenous Protected Area is made up of 1,700 hectares of significant wetlands and stony rises right next to the historic lava flows of Mount Eccles National Park in south-west Victoria.

The area is part of the Budj Bim National Heritage Landscape listed in 2004. Lake Condah was included in the listing because of its outstanding cultural heritage value for all Australians.

Like other volcanic plains properties next to it, Lake Condah is home to nationally significant species including tiger quoll, intermediate egret, great egret, powerful owl, barking owl and common bent wing bat. The property's unique contours and landscape formed when Mount Eccles started erupting some 20,000 years ago. Gunditjmara people share the knowledge of their ancestors and elders about how an ancestral creation revealing himself and creating the Budj Bim landscape.

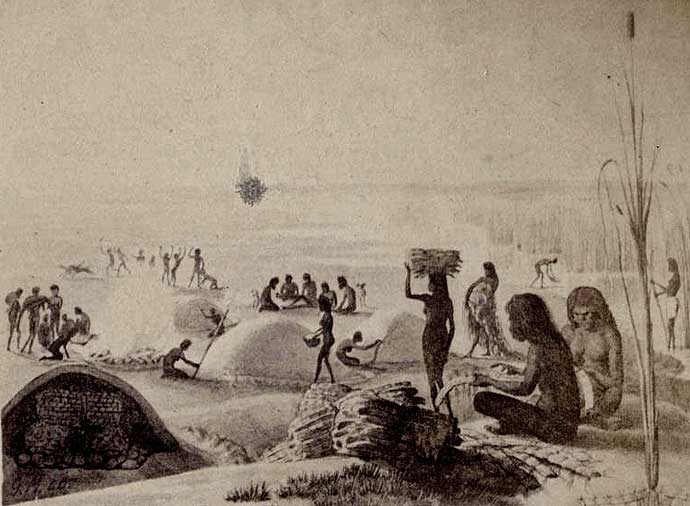

Source: State Library of Victoria

Enlarge image

Brough Smythe Papers, c 1840

Blacks, about 50 miles N.E. of Port Fairy, by what is termed the Scrubby Creek, before settlers came among them had a regular Village. My informant who drew this states that there were between 20-30 evidently some of them big enough to hold a dozen people, their shape as under an aperture at top to let out smoke, which in rainy weather they covered with large sod, The form like a Bee Hive about 6 feet high + or - and about 10 feet in diameter. An opening about 3 feet for a door way which they could close at night with piece of bark. There, blacks made regular dams in creeks to catch fish. They could make straw nets and their baskets were different. About 1839 settlers first began to settle in this area. About May 1842 a station was formed on the opposite side of the creek to this Aboriginal settlement ...

Enlarge image

Brough Smythe Papers, c 1840

Download: Brough Smythe Papers pdf

The Kerrup Gunditj clan at Lake Condah had traditionally engineered an extensive aquaculture system at Lake Condah. Other Gunditjmara clans along the Budj Bim landscape worked together to establish kooyang (eel) trapping and farming systems, developing smoking techniques to preserve their harvest - probably one of the first cultures in the world to do so.

They continued to live and work on their country in a highly complex society until Europeans arrived in the region. As pastoralists moved further into south-west Victoria, the stone country of Lake Condah became a sanctuary for Gunditjmara people providing eels, possum and kangaroos for the families.

Evidence of the stone trap systems that Gunditjmara used for thousands of years still remain on the property.

A goal of the Gunditjmara is to engage their people back in the landscape, in eel and fish havesting using traditional methods, and use their traditional knowledge to support land and water management.

Today the Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation oversees the management of the property on behalf of the Gunditjmara.

The corporation has invested in many projects to improve the health of the cultural and natural heritage of Lake Condah, including wildfire prevention measures and management plans, development of tourism ventures, conducting plant and animal surveys, reviving traditional ecological knowledge and measures to protect the water levels at Lake Condah.

Like all Australia's Indigenous Protected Areas, Lake Condah IPA is part of the National Reserve System - our nation's most secure way of protecting our cultural heritage and native habitat for future generations.

Declared in April 2010, Lake Condah IPA is managed under the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Category VI, as a protected area with sustainable use of natural resources.

Heywood, Victoria | Lake Condah Indigenous Protected Area - Declared in April 2010

Gunditjmara will conserve Lake Condah. It is an important Gunditjmara place and we have fought hard over many generations to see it returned to us so that we can heal this land. Gunditjmara will restore the natural abundance of the lake and its native plants and animals for us today and our future generations

Source: environment.gov.au

First Nations people using clay/earth kilns to cure plants. Sketch by explorer Wilhelm von Blandowski c1849-1859 - Murray Darling region

Aboriginal Village

ABC Catalist 13 March 2003

Archaeologist, Dr Heather Builth investigated the Gunditjmara's claims. And remarkably she found a great deal of evidence to support them ... the remains of 100s of huts, more than 75 square kilometres of artificial channels and ponds for farming eels, and smoking trees for preserving the eels for export to other parts of Australia.

Artist impression of hut: ABC Catalist

Narration: At Lake Condah in western Victoria, there's a mystery. We're told aborigines were nomads. Yet here the aborigines, claim their ancestors lived in a village. A village so sophisticated, they farmed eels in these swamps, they processed them and even exported them across the country. If true it would seriously challenge our understanding of aboriginal history.

Ken Saunders: We weren't nomads. We didn't wander all over the bloody place and gone walkabout. We had an existence here.

Professor Peter Kershaw found some tantalising evidence in this snake-and-leech-infested swamp. He took a soil sample from the bottom. Because soils are laid down gradually, drilling down several metres is like going back in time.

Professor Peter Kershaw: This is healthy peat material. It suggests that it's accumulated under shallow water and there's been constant deposition. As we go towards the top here, you can see it's getting very kind of fine-grained sediment. It's very greasy.

Narration: It's greasy because the lake was continually churned up while this soil was being laid ... possibly churned up by human eel farmers.

Professor Peter Kershaw: This doesn't occur naturally. It had to have some help. People have been here or that is the most likely explanation.

Dr Heather Builth, found more enticing clues that there could be an ancient eel farm here. There appeared to be countless artificial channels crisscrossing this landscape.

Dr Heather Builth: This has had to be excavated. This channel is artificial channel that has come through the lava flow through the sheer rock to bring the water from this swamp into that swamp.

Narration: In fact there appeared to be artificial ponds here as well. But it was hard to make sense of all this because the entire area was drained in the 1800s when the Europeans moved in. But Heather had an idea. She measured up every little hill and valley in the landscape, entered all the information into a geography simulation programme and then re-flooded the land on computer.

That way she could see where all the artificial channels led. The computer programme revealed a dazzling picture. An artificial system of ponds connected by canals, covering more than 75 square kilometres of the landscape.

Dr Heather Builth: I realised there was something pretty clever going on here. The swamps were joined and there were channels joining the wetlands to the river and there were channels continuing on to the sea across the whole length."

Narration: Heather was starting to believe there could well have been an ancient eel farm here. Meanwhile, the soil samples revealed more exciting results when they got back to Peter's Monash University lab. Pollens were extracted, and they showed water plants had suddenly appeared in the record - just what you'd expect if humans had suddenly constructed an artificial ponding system. But the most staggering result came when he soil samples were radiocarbon dated. The artificial ponds it appeared, were created up to 8000 years ago.

Dr Heather Builth: Yeah that is pretty amazing historically, prehistorically in the world about controlling a resource in aquaculture.

Yeah - it could be one of the oldest systems in the world."

Narration: Of course, none of the scientific discoveries surprised Ken. He says the whole countryside here is dotted with eel traps.

Ken Saunders: We used to trap eels ourselves and use the eels traps. And some of the young fellas today still use the eel traps. So the eel traps were part of our diet. I still eat the bloody things today.

Narration: The telltale sign of an eel trap is two piles of rocks in straight lines. Woven basket-like nets were placed in the gap where the water once flowed.

Dr Heather Builth: This would have come in here, and understand that it would've been about four times as big as this now, and it would've fitted in. There would've been a frame here - a wooden frame and this would've gone through the frame like that so it would've been filling up a bit. It was a big enough collar to catch the eels. So what it meant was they could only come out one at a time and so someone was here to catch the eels as they came out and grab them bight them on the back of the neck, kill them put them in the basket.

Narration: Evidence that 8000 years ago the Gunditjmara had a large-scale eel farm here was already enough to rock the archaeological establishment. But what about Ken's claim that his people actually had an industry, and were exporting their produce?

Heather had noticed there were a lot of these trees that had obviously had fires in them. Could it be the Gunditjmara smoked eels in them, to preserve them for export? She took a sample deep down where the soil was contaminant-free, to see if a lab could find traces of eel. But after putting it in the fridge overnight she was greeted by a remarkable surprise the next morning.

Dr Heather Builth: The next day, when we went in to open the door, the whole room stank of smoked eel and that was the eureka moment. And the fact that all these trees, if people had been using them, that means there was preservation. Suddenly the whole picture changed. Gunditjmara weren't just catching eels; their whole society was based around eels. And that to me was the proof. That was it.

Narration: This wasn't just one of the earliest farming villages ... . this was an ancient industry. And that put the Gunditjmara in a totally different category.

Dr Heather Builth: A specialisation had developed here of eel production. And these eels could have gone out long distances and they would have been the currency these people bargained with. I think what we had here was a hierarchical structured society. We had chiefs with lots and lots of power.

Narration: But if this was a village, where did the inhabitants live? The answer to that lay with these stones scattered all over the landscape. Many of them seem to lie in circular patterns. Archaeologists had dismissed them as natural formations, but could they be the foundations of ancient huts?

To prove that, Heather painstakingly measured and weighed each of the stones in some of these structures. And sure enough she found they were too uniform to have been stacked up by nature.

Graham: This is one of the stone huts?

Heather Builth: This is one of the stone houses.

Narration: They had to have been built by human hands and the most likely explanation is they were dwellings.

Graham: How many stone huts do you think were in this area?

Dr Heather Builth: I have myself have seen hundreds.

Graham: We're talking about ... I mean that's a village ...

Dr. Heather Builth: Yes, we're talking villages

Graham: Villages!

Heather Builth: Villages

Lindsay Saunders: You can see there about two metres. By about a metre high. The door would have been facing east, away from the weather coming in from the west. This would have housed about two or three people."

Narration: This is what the huts might have looked like, based on historical accounts and the materials that were available. Wooden boughs sat on top of the stone foundations and they were covered with peat sods for strength and reeds for waterproofing. What you're left wondering is ... How did archaeologists miss all this? Heather believes it's because everything disappeared very quickly when European farmers moved in.

Dr Heather Builth: A lot of them had a military background and they knew how to get rid of aboriginal people pretty quickly.

Narration: While the scientific discoveries don't surprise Ken, he hopes they will help his people.

Ken Saunders: If we can get National Heritage Listing - which we will get - we can then rebuild and recreate the fish traps again.

Narration: The Gunditjmara eel-trap-weaving skills are still being handed down, and Heather now knows how the eel farms operated. Her science may just help Ken's people realise their dream.

Ken Saunders: Well you couldn't have a blackfella telling that story. So to prove it we had to have a white person doing the scientific research to say this is real.

Topics: Archaeology & History

Researcher: Robyn Smith

Dr Heather Builth Email

Postal address: RMB 7460, Coustleys Rd, Homerton, Via Heywood, Victoria 3304

Ph: 03 55272051

Professor Peter Kershaw Email

Director of the Centre for Palynology and Palaeoecology,

Geography & Environmental Science, Monash University, Melbourne

Tel: 03 9905 2927 - Ken Saunders Co-ordinator of Lake Condah Sustainable Development Project

03-55784272

Story contacts information may be out of date - Original publishing Date 13 March 2003 - posted on Sovereign Union 18 March 2014

The First Race: Out-of-Australia, Not Africa!

The First Race: Out-of-Australia, Not Africa!

Book argues against Aboriginal 'hunter gatherer' history

Book argues against Aboriginal 'hunter gatherer' history

Australia's first people were Australia's first farmers

Australia's first people were Australia's first farmers

![]() Article - Research: 'Biggest Estate on Earth' by Bill Gammage

Article - Research: 'Biggest Estate on Earth' by Bill Gammage

First Nations 'Fire Hunting' benefits small-mammals: Research

First Nations 'Fire Hunting' benefits small-mammals: Research

![]() Article - Research: Stanford University USA

Article - Research: Stanford University USA