How First Nations people survived through the Ice Age

Wes Judd Australian Geographic 27 September 2013

Population numbers plummeted due to harsh conditions at the peak of the last Ice Age, says a new study.

A study has revealed how First Nations people coped with the last Ice Age, roughly 20,000 years ago.

Researchers say that when the climate cooled dramatically, Aboriginal groups sought refuge in well-watered areas, such as along rivers, and populations were condensed into small habitable areas.

Professor Sean Ulm, lead author of the research at James Cook University in Townsville, says the vast majority of Australia was simply uninhabitable at this time. "Forests disappeared, animals went extinct; major areas of Australia would have been deprived of surface water."

This map estimates the areas in which Aboriginal groups congregated during the last Ice Age. (Photo: Peter Veth)

How humans coped with the last Ice Age

To understand how Aboriginal people responded to the conditions, a team of experts from Australia, England, and Canada used the radiocarbon dates of thousands of archaeological sites to study the distribution of people across the landscape over time.

The findings, published recently in The Journal of Archaeological Science, suggest that about 21,000 years ago, almost all people in modern-day Australia migrated into smaller areas, abandoning as much as 80 per cent of the continent.

"In Lawn Hill Gorge in northwestern Queensland, at the coldest point of the last glacial period, all of the stone, raw materials and food remains are exclusively from the Gorge area," says Sean. "This indicated very limited or no use of the surrounding broader landscape."

This massive consolidation had drastic effects on the population as well. "There was likely a birth rate decline of over 60 per cent," says Alan Williams, a PhD student at the Australian Nation University who worked on the study. "It would have been very ugly."

Can humans cope with climate change?

Sean says the next step would ideally be to study the resulting cultural shifts, however, this may prove to be difficult given that close to one third of what was Australia at the time of the Ice Age is now underwater. "By 10,000 years ago, sea levels were visibly rising, sometimes on a daily basis," says Sean.

Extreme changes in the environment continued for thousands of years, and Aboriginal life readjusted in the process. Sean says this makes it unlikely that researchers will ever know the full societal ramifications of the Ice Age.

What the study does reveal, however, is that humans have withstood massive climate change on this continent in the past, and this might prove vital for preparing for future events.

"A lot of the current climate reports that we read about in Australia...their records only go back a couple of hundred years," says Sean. "That's a very short time span to base our model for future climate change on."

Sean adds that, thanks to studies like this, archaeologists may soon have the potential to extend these data sets.

John Ross The Australian 24 April 2013

A new study questions the 'saturation' theory that Aboriginal populations rapidly achieved 'ethnographic' densities.

Australia's prehistoric population suffered an "astounding" decline at the peak of the last ice age, with food and water shortages more than halving the number of inhabitants, a new study suggests.

Alan Williams, an archaeological consultant and PhD candidate at the Australian National University, said cool and "incredibly dry" conditions between about 21,000 and 18,000 BC had cut a swathe through the population, which at that time numbered around 20,000.

"The data suggests a decline of about 60 per cent, which is a fairly astounding number," Mr Williams said.

"If you look at contemporary data, we've just reached 23 million people in Australia. It would equate to something like 14 million people being lost over 3000 years."

Mr Williams's study, published today in the biological sciences journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, is the first reconstruction of Australia's prehistoric population flows based on radiocarbon data.

He estimated there were about one million people in the continent at the time of European settlement in 1788. But the carbon data indicated the population had fallen about 8 per cent since a peak 300 years earlier, suggesting introduced disease - possibly smallpox brought in by Makassars from Sulawesi in Indonesia - could have had an impact.

The study found the population changed very slowly over the last 40,000 years or so, never numbering more than a few tens of thousands, before climbing solidly about 12,000 years ago.

Mr Williams said the inhabitants hadn't occupied the entire the continent before then, although exploration had happened.

"They'd have had one person per 300 or 400 square kilometres, which is probably less than we saw in the deserts in the recent past. It would have been fairly hard to colonise the continent, but people were clearly moving around because we've got (radiocarbon) dates very early across the whole country."

Mr Williams said that while the study's findings were "speculative", it built on research over the past five years that had established new techniques for combining radiocarbon data and removing error limitations.

"The availability and level of radiocarbon data has increased exponentially," he said.

Paul Heinrichs The Age 13 August 2006

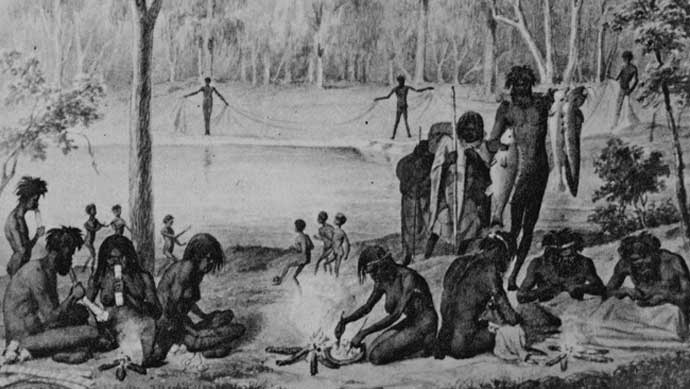

(Photo: The Age)

New archaeological research has severely dented the controversial theory espoused by Australia's high-profile scientist and intellectual, Tim Flannery, that early Aborigines wiped out Australia's megafauna.

A combined Melbourne-La Trobe university team has found strong evidence that cold, arid climates during the last Ice Age had already wiped out the megafauna before evidence of humans activity is evident - in one place, at least. Giant marsupials such as a 3.5-metre kangaroo, a hippopotamus-sized wombat-like diprotodon, huge "killer possums" (also known as marsupial lions, or thylacoleo), and giant emu-like birds, genyornis, roamed Australia until about 50,000 years ago.

Most of them were slow-moving animals, and their extinction at what was thought to be about the same time as the first wave of Aborigines appeared in Australia has caused conjecture that early hunters were responsible ... more ...