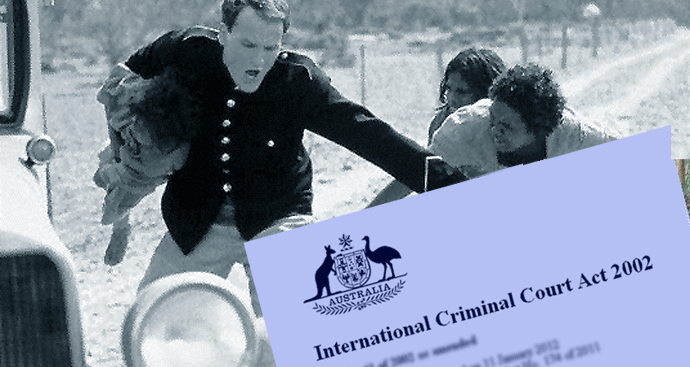

Time to fully import law against genocide - Stolen Children crisis

Australia has still not fully imported the Genocide Convention into domestic law.... only the Attorney-General can begin a genocide case and if he/she refuses there is no right of appeal and no reasons need to be given. [268.121 - 268.122]. This is contrary to the intent of the long-standing Genocide Convention, which Australia was the third country to sign.

...

We cannot allow the occupying state to continue to decide our future. We must assume total control and administration of our own working solutions and thereby rid ourselves of the occupier's strategic plans of assimilation through its bureaucracy.

The solution is to bring back customary social practices within each Nation through the process of real self-determination at all levels and our people must effectively take ownership of our own solutions.

30 November 2017

Family Matters: Proposal for deletion of Sections 268.121 - 268.122 of the International Criminal Court (Consequential Amendments) Act 2002

The release on 29 November 2017 of The Family Matters Report 2017 details the 'escalating national crisis' of the rate of removal of First Nations children from families.

From our perspective the core issue is being left out of the debate:

- Removal of children from the group is one of the five definitions of genocide.

- The alarming rate of the removal of First Nations children 'from the group' is only possible because the Commonwealth of Australia has not imported the full force of the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

- When Australia applied to join the International Criminal Court (ICC) several UN member states objected because Australia did not have a domestic law against genocide. The federal parliament hastily passed the International Criminal Court (Consequential Amendments) Act 2002 but fudged it, so that only the Federal Attorney-General can begin a genocide case and if he/she refuses there is no right of appeal and no reasons need to be given [268.121 - 268.122].

- Genocide is the worst crime in the world and ratification of the Genocide Convention means that a genocide case is meant to be able to be initiated in any court by anyone.

- We have raised this matter internationally in several fora including with the former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Navanethem Pillay, who has been a judge on the ICC.

- Countries are not considered civilized if they do not have an effective law against genocide.

Deletion of Sections 268.121 - 268.122 of the International Criminal Court (Consequential Amendments) Act 2002, which violate the 1948 Genocide Convention.

- Proceedings for an offence under this Division must not be commenced without the Attorney General's written consent.

- An offence against this Division may only be prosecuted in the name of the Attorney General.

- However, a person may be arrested, charged, remanded in custody, or released on bail, in connection with an offence under this Division before the necessary consent has been given.

268.122 Attorney General's decisions in relation to consents to be final

-

Subject to any jurisdiction of the High Court under the Constitution, a decision by the Attorney General to give, or to refuse to give, a consent under section 268.121:

- is final; and

- must not be challenged, appealed against, reviewed, quashed or called in question; and

- is not subject to prohibition, mandamus, injunction, declaration or certiorari.

-

The reference in subsection (1) to a decision includes a reference to the following:

- a decision to vary, suspend, cancel or revoke a consent that has been given;

- a decision to impose a condition or restriction in connection with the giving of, or a refusal to give, a consent or to remove a condition or restriction so imposed;

- a decision to do anything preparatory to the making of a decision to give, or to refuse to give, a consent or preparatory to the making of a decision referred to in paragraph (a) or (b), including a decision for the taking of evidence or the holding of an inquiry or investigation;

- a decision doing or refusing to do anything else in connection with a decision to give, or to refuse to give, a consent or a decision referred to in paragraph (a), (b) or (c);

- a failure or refusal to make a decision whether or not to give a consent or a decision referred to in a paragraph (a), (b), (c) or (d).

- Any jurisdiction of the High Court referred to in subsection (1) is exclusive of the jurisdiction of any other court.

As a consequence of life inside the belly of the genocide, suffering from trauma, grief and loss has been normalised for our people and the solution here is not a blame game against the victims of historical circumstance.

Our people are burdened by oppression, welfare dependency and lack of resources.

This issue will not go away.

We cannot allow the occupying state to continue to decide our future. We must assume total control and administration of our own working solutions and thereby rid ourselves of the occupier's strategic plans of assimilation through its bureaucracy.

The solution is to bring back customary social practices within each Nation through the process of real self-determination at all levels and our people must effectively take ownership of our own solutions.

Some previous submissions:

Palais Wilson, 52 rue des Paquis, CH-1201 Geneva, Switzerland

24 May 2011

Submission by Michael Anderson,

Leader of the Euahlayi Nation

Co-founder of the 1972 Aboriginal Embassy in Canberra

and Convenor of the New Way Summit & Sovereign Union

Your Excellency,

... No effective law against Genocide

We are requesting that the UN Human Rights Commission strongly recommends that the Australian government imports fully the Genocide Convention into domestic law.

24 May 2011

... We demand the Commonwealth of Australia enacts the full force of the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. The new legislation must take away the necessity of the Attorney-General to approve a case against genocide, as currently enshrined in the International Criminal Court (Consequential Amendments) Act 2002.

in conjunction with

International Educational Development

UNITED NATIONS

Sub-Commission on Promotion and

Protection of Human Rights

Fifty-second session

Agenda item 7

11 August 2000

Human Rights of Indigenous Peoples

[The first part of this statement is made for and on behalf of the Nyoongah Ghurradjong Murri of the Euahlayi Nation and the Sovereign Union of Aboriginal Peoples of Australia].

This issue was presented to the Australian Courts due to the passage by Australia of first the Native Title Act of 1993 and then the Amendment Act of 1998 -- acts that ought to be named the Native Disentitlement Act and the Further Native Disentitlement Act, for the 1993 bill extinguished between 80 and 90% of Aboriginal land claims and the second severely diminished the remaining 10-20%. Any person who has followed the debates during the 18 years of the Working Group understands the profound relationship of Indigenous peoples to the land. The Aboriginal Peoples of Australia have shown over and over that from the time of the "Dreaming" (creation) the Aboriginal Peoples have a synergistic and totemic relationship with the land and are ordered by the Creator to protect and sustain this land and all that is upon it -- animate and inanimate, animal and plant, rock and sky and water. Removing Aboriginal land from the protective control of the Aboriginal Peoples means not only the destruction of the land but also of the Aboriginal Peoples. It is this profound relationship that must be protected in order to prevent the destruction in whole or in part of the Aboriginal Peoples and their culture. And it is the removal of these lands that brought forth the law suit alleging genocide. As most experts, including Rodolfo Stavenhagen, have attested, destruction of the land base of Indigenous Peoples constitutes a contemporary form of genocide -- genocide/ethnocide. The Plaintiffs in the Australian case had, thus, an arguable claim. And in addition, the UN Committee Against Racial Discrimination had decided on 18 March 1999 that the 1998 Act was, at the least, discriminatory. (CERD/C/54/Misc.40/Rev.2).

The several courts in Australia that ruled on this claim insisted that although Australia has ratified the Genocide Convention it has not incorporated the Convention into municipal law. Thus, says one judge: 'I have concluded that no offense of genocide is known to the domestic law of Australia.'* This opinion defies the jus cogens status of genocide -- existing outside the specific treaty -- as well as the erga omnes nature of genocide as set out by the International Court of Justice in is ruling in Barcelona Traction case. Even worse, the counsel for the Prime Minister in the case argued that the Genocide Convention was deliberately not incorporated. As states The Weekend Express: " accused war criminals ... who have become Australian citizens, will not be effected ... because politicians fear that [incorporation] . . . will also open the way for the Aboriginal claims of genocide."

We note to the Sub-Commission that the genocidal acts in question arise long after the Genocide Convention was promulgated and the customary law of genocide clearly settled on the points at issue.

We also point out that all States have an affirmative duty to act on allegations of genocide and we expect them to do so in this case.

*Justice Crispin, ACT Supreme Court in Nulyarimma v Thompson:

'I have concluded that no offence of genocide is known to the domestic law of Australia.' [para 73] (8 September 1998)

see also: Nulyarimma v Thompson (includes two corrigenda dated 2 September 1999) [1999] FCA 1192 (1 September 1999)

Contact: Ghillar Michael Anderson

Contact: Ghillar Michael AndersonConvener of Sovereign Union of First Nations and Peoples in Australia and Head of State of the Euahlayi Peoples Republic

Contact Details for Ghillar