Aboriginal Smoke Signalling and Signalling Hills in Resistance Warfare

Although some non-aggressive uses of smoke signalling and signalling hills may have been misconstrued by early settlers, it seems likely that signal hills and their codes of signalling were at times applied for defensive and offensive purposes during the Frontier Wars. From our brief examination, it would seem that smoke-signalling was more than sophisticated enough to serve inter-tribal communication and coordination for attacks and speedy retreats. Moreover, there are several early accounts that attest to its use for exactly that purpose.

Dr Ray Kerkhove October 2015

Signalling hills and lookouts were of immense importance for Aboriginal groups. They were often pivotal landmarks in the Songlines landscape, major means of communication and education, and tools for co-ordinated hunting or fishing. Their importance is reflected in some Aboriginal place names, for instance Nildottie in South Australia, which actually meant "smoke signal hill."1

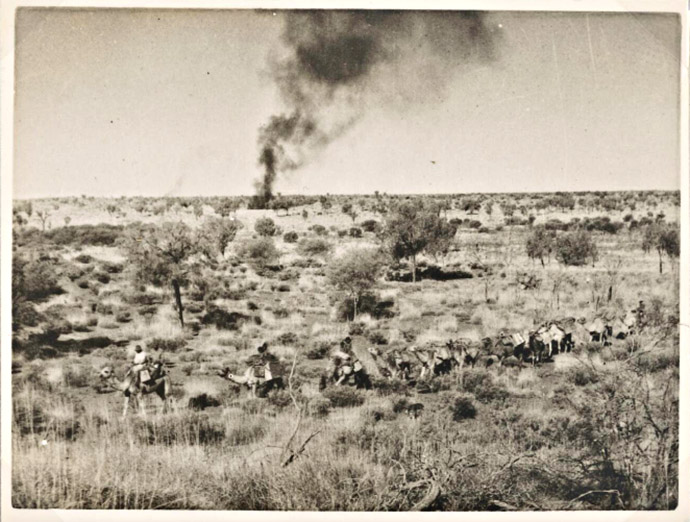

Historically, Aboriginal signalling lookouts are of interest for the role they seem to have played in co-ordinating resistance activities. Signal hills were reportedly utilized for monitoring and communicating the movement of both enemies and strangers, and for coordinating attacks when necessary.

When an expedition (the Spitfire) was launched up the Burdekin River and to Magnetic Island in 1860, the crew claimed they saw " ... several signal fires about the Coast ... " (italics mine). As soon as the party reached Magnetic Island, their Aboriginal assistants " ... .immediately went off to light signal fires"2 - apparently in response to the on-going messages.

In fact, it was common for explorers to note on-going communication between signalling hills. For instance in South Australia in 1840, an exploratory party witnessed how one 'smoke' had "been answered from Gawler Point ... . Smokes had been observed in the other directions."3

A discussion with Dr Ray Kerkhove, who has undertaken extensive research into First Nations warfare in Queensland in the 19th century.

Ray speaks with Phillip Adams

(ABC RN 'Late Night Live' 11 March 2015)

The fact that such signals could be used for aggressive action was soon experienced by the same South Australian party. According to them, through smoke-signalling, a massive regional burn-out was conducted which almost ousted and incinerated their group4 . Similarly, near Bowen in Queensland in 1862, signal hills were according to witnesses employed to rapidly mobilize hundreds of warriors from other locations:

(They) attacked our little camp twice in one afternoon in two different mobs of about 100 strong each, and, from the signal-fires that had sprung up on many hills, ... .we had most unpleasant proof, not only of their capabilities of conceiving, but of executing "a concentrating movement" with most disagreeable rapidity. On the occasion referred to by your correspondent, there were about 300 armed blacks collected within eight miles (italics mine).5

Signal hills probably were also claimed to protect local groups during the Frontier Wars. When police launched a punitive patrol around the Pine Rivers and Sandgate areas in 1857, the camps are reported to have smoke-signalled "up and down the coast", with the results that the police encountered empty encampments on arrival.6

(trove - National Library of Australia)

In my own on-ground investigation of former (historic) campsites around Brisbane during the last four years, I found that they are often located very near some high point or hill: a headland, knoll etc. From the camp or at least from that nearby hill, another significant high point could usually be clearly seen - often one I knew to be located next to another camp. For example, a hill near the St Lucia camp looked towards Mt Gravatt hill (which lay beside a series of camps on Logan Road); a hill near the Rocklea camp looked towards the Sunnybank camp/ Toohey Hill; and the beach at the Gateway bridge camp looks out at Mt Samson. Thus a virtual relay of signals could indeed be possible.

The lookout-hills were certainly reported as signalling news of the progress of attacks, as this 1861 account of activities in South Australia records:

... On the evening of the sad event, a large beacon fire and thick smoke were observed on the distant hills. This the troopers understood to be a means by which the natives were telegraphing news of the murder. The signals of the natives were so very singular and marked that they could not fail to attract the notice even of Europeans. A large number of the natives stand round the fire with branches in their hand, which they simultaneously place in the flames till ignited, and then raise on high. This is done three times, thick smoke rising on each occasion, and is imitated by the blacks at a distance, and so the news of a victory is sent often 100 miles in a day. The troopers understood the signs well, and came in to Lieutenant Cave holding up their hands and saying "All white fellow killed!" (italics mine)7

Of course, it was quite possible that explorers and early settlers thought smoke-signalling was aimed against them when it was merely communicating 'regular business.' Certainly some of the 'burn outs' interpreted as aggressive actions may simply have been co-ordinated seasonal burn-offs which explorers were unlucky enough to be caught up within.

Early accounts concur that Aboriginal smoke signalling was mostly used to convey " ... well-understood message(s) of welcome or warning, of invitation or defiance, of mourning or rejoicing ... . spread with amazing speed." 8 It provided the best means for groups to " ... .quickly communicate with one another over wild and rugged country ... . 9 Eli Rys summarizes these uses as follows:

- Invitation to fish or hunt

-

Warnings:

- major well has dried up

- neighbouring tribes are on the war-path

- strangers present within hunting grounds10

We know from Thomas Welsby - an early settler familiar with the peoples all over Moreton Bay - that the use of signalling hills for hunting and fishing extended to informing and perhaps co-ordinating large-scale fishing drives:

(On the conical) Pyrnn, Pyrnn Pa, meaning little hill ... .the (Aboriginal) fishermen of the Bay would sit - on its summit, and use fire or smoke as a signal to their comrades in the distance that fish were at certain places about. From its top could also be seen all the fringed foreshore of the island towards Dunwich, and, at low water, the banks along and upon which the traveller walked or rode on his journeyings to and from Amity."11

Smoke signals from lookouts were regularly used to summon groups over vast distances - for instance, to the bunya festival.12 On the Bunya Mountains the signalling fires were generally lookouts, and the Traditional Owners of that region acknowledge that many of the Bunya Mountains lookouts and tracks to them served this purpose in pre-Settlement and early Settlement times.13 Mrs Bennie - an early resident of the area - surmises that by this means, groups from even hundreds of kilometres away would turn up "almost simultaneously" at assigned spots.14

Despite such harmless agendas, it is easy to see how the same signals could be employed if necessary to amass hundreds of warriors from several groups at fairly short notice. Many attacks on stations were described as involving 200 to 700 warriors - figures that seem inexplicable given the size of most local groups (a clan estate was usually 40-80 persons), but which were traditionally common for inter-tribal 'tournaments.' The latter were indeed organized through smoke signalling:

... an old chief ... . said there would be a fight the next day, he saw two ' spiral smokes' produced by turning skins round in a peculiar manner. The next morning there were from 700 to 800 armed natives assembled near them who had come up in canoes...15

Moreover, we should not assume that European settlers were incapable of determining whether a signal was friendly or hostile. During the early Colonial period, it seems that many Europeans - both squatters and persons within the border police - grew accustomed to 'smoke signal language.' A graphic incident is given by Tooth (a Wide Bay settler) concerning the 1860s. He sent one of his Aboriginal assistants up a tree, evidently in an elevated spot:

"We sent Sambo up a tall gum tree, 'to look out;' he was soon down again and reported. "Mine milmil three 'fella smoke close tip, like it more furder station, one pfella cob-lion two pfella nerang-ie smoke like it salt water." Interpreted this meant: he had seen three columns of smoke just the other side of the station, and one big column and two smaller ones near the sea. My brother at once exclaimed: "So there's a traitor in camp, and he has signalled that the three of us have started out, but what does one-big and two small smokes mean? That is a fresh signal." Although both of us were well up in "smoke language" or "signalling," neither knew what that meant (italics mine).16

Another account worth considering on this issue comes through William Clark's interview in 1912 with Ltnt Fred Walker - the first Commandant of the Native Police force. William Clark, as an early settler of the Dawson River region, personally experienced the frontier wars. The following information he gleaned from interviewing Ltnt Walker. Walker was adamant that smoke-signalling was indeed used to organise attacks and avoid his Native Police. He alleged that his troopers understood a lot of the 'language' of smoke signalling and that this allowed his forces to be more effective than white vigilantes:

(The smoke-signalling was) ... used by blacks when travelling to communicate with their detached mobs ... . The yabber or talk that was going on between them ... often disclosed the locality of meeting places ... 17

According to Gaiarbau (Willie MacKenzie - a Kilcoy Aboriginal) signalling hills could be usually identified by their bonfire pits, which had a circle of stones about 4 feet wide and 4 feet high, and it seems that there were 'signalling specialists' - who Gaiarbua says were bora councillors.18 This suggests that the system had rather formalized signalling points and required some in-depth knowledge.

In 1893, Mr. A. T. Magarey presented a paper to the Royal Geographical Society in Adelaide that still remains one of the keystones of our knowledge on Aboriginal smoke-signalling. He argued that smoke-signalling was an extremely sophisticated mode of communication. As he himself noted, it relied heavily on variations of smoke colour, the width of columns and the effects that could be achieved such as "puffs, balloons and parallels."19 Magarey argued that the system was almost as detailed as telegraphy. His audience was sceptical, so he had a NSW Aboriginal (Mark Wilson) speak on the topic as well:

... those trained in the work could play on a fire just as a man would manipulate a keyed musical instrument ... Mr. Mark Wilson, an aboriginal native from Point Macleay ... gave some interesting information as to the smoke signals of the lakes and Murray River tribes. For instance, if a corroboree was to be held for which the river tribes were coming down south a fire, sending up a dark column of smoke would be lighted at Mannuth as a signal to the tribe at Point Macleay. The Macleay tribe would signal to the other lake tribes and all would assemble at Wellington, where the gathering would be held. He then described the signals for war, death and losses in the bush; and also how fires were built for night signals, and how puff smoke balls were made. These latter were caused by holding the smoke under a skin or board and then suddenly releasing it, when it would shoot up in the form of a 'puff.' ... (There were also) straight smoke signals, smoke balls, and flashlights made from the inner bark of certain trees.20

William Clark's interview with Ltnt. Walker even describes a specialized 'chimney' built to better shape the smoke from signalling fires:

They first took the bark from saplings in tubular shape. On the summit of some high hill or range they made a smoke fire, and placed a cylinder of bark over the smoke. They lengthened the improvised chimney stack by placing additional lengths of bark within each other. This bark funnel was secured perpendicularly against some high tree by native cord made of fibrous bark called boogaroo ... .. I have often seen these signals on some distant range, the compressed smoke, shooting up to great altitude in spiral columns, and visible for long distances.21

Military intelligence requires a level of secrecy to be effective, which is why codes have often been developed for warfare. It is worth noting that the meaning of Aboriginal smoke messages varied from region to region. There was a 'code' for 'insiders' (moving parties within a single tribe) and another for communicating with outside groups: "every tribe had its own particular code which was used for short distance signals ... (but) there was an inter-tribal code understood by all the tribes for long-distance signals ... "22

Moreover, it was possible to alert only some groups to a message and deny others, by using this 'insider language' and pre-warning the intended party:

The attention of the other tribe or tribes would be drawn to the fact that it was desired to send some signals, by lighting a signal fire below the top of a hill in the direction of the tribe/s to whom the signal was to be sent. Its light would be prevented from being seen in any other than the desired direction by shields of large pieces of bark. Such fires could be seen for a distance of 25 miles or more (italics mine).23

Furthermore, it seems that signalling relied on a very specific relay of hills and prearranged 'watching' for signs from those hills. Thomas Hall (1845-1928) - a Warwick pioneer- remembered that certain hills were used by certain groups, and that signal flowed between them according on pre-arranged times:

... the aboriginals had signalling mountains belonging to each tribe on which smoke was made to rise in prearranged waves, the code being perfectly understood by the tribes. The principal station for the Blucher tribe when signalling to the Coastal tribe was the mountain at the head of Emu Creek, adjoining the Southern end of Mt Huntley. The Richmond tribe had Wilson's Peak, while the McIntyre River tribe had Mt Huntley at the head of the Swan Creek or Cunningham's "Logan Vale." In this way the tribes could pass word along over long distances many days in advance of the white man's earliest opportunity, and were always prepared for the whites. Our nearest approach to this is the Heliograph. I have often watched these smoke signals with te permission of King Darby, when the Blucher were communicating with the Fassifern Tribe.24

Such checks and balances aside, is it possible for smoke-signalling to convey sufficient data to be effective in inter-tribal strategies against settlers? As the meaning of signals varied from place to place, this is difficult to establish. The brief survey of literature attempted above suggests it is possible to reconstruct the following 'general' signals, which would all have been useful in decision-making when dealing with an influx of armed settlers:

| ► Slender column, pale smoke = distress - sickness or accident: "one fellow sit down ill" |

| ► Heavy column, white smoke (short distance) = "a friendly tribe is coming to yabber" |

| ► Heavy column, white smoke (long distance - from grass piled up) = someone has died (this fire must be created by facing away from the beacon - using a trail of dry grass as a wick). |

| ► Slender column, dark smoke = invitation to a conference concerning tribal grievance or threat of war. |

| ► Dense smoke, rising 1500 - 2000 feet (large quantity of fuel, overlaid with green bushes) = strangers have crossed from the territory of the signallers to that of their neighbours. 25 |

| ► Row of several columns, even distance apart = corroboree invitation |

| ► Two columns ascending continuously (unbroken for 1+minute) = danger26 |

| ► Straight column without succeeding cloud = enemy/ stranger coming |

| ► Column broken regular intervals = friends coming Single column, then pause, then single puff (cloud) = invitation to join hunt27 |

We know further that it was even possible to convey numbers through series of puffs:

Belches of smoke, or a series of small clouds, signifying numbers, are sent up by covering the fire with a skin or sheet or soft bark held by two persons, or by a thick bush when there is only one operator, and uncovered smartly. Spiral columns are made by gently whirling a skin or sheet of bark around the ascending column.28

Early Illustration (unknown source)

(not part of Dr Ray Kerkhove's Paper)

Near Toowoomba, there is a registered outlook at the Second Range Crossing which is held as particularly significant by the local Indigenous groups. Its exact purpose is not known, but elders recall it was especially important and have requested a detour in the Toowoomba Bypass to preserve it.

Most probably, this lookout was involved in the coordinated resistance activities of the 'Mountain tribes' (Darling Downs, Lockyer Valley, Cunningham's Gap and other areas) during the 1840s and 1850s under the leadership of 'Old Moppy,' Multuggerah and others are mentioned in several early accounts. It looks across the valleys below the Main (Dividing) Range, down which settlers descended and along which main supply routes featured.

In 1842, close to Toowoomba, early settler John Campbell and his party fought off a raiding party along the road up Gorman's Gap to the Main Range. He noted that the attack was being organised through signalling hills on the Main Range very close to the lookout. He recalled that: "all this time we could hear their signals passing alongside the Sugar Loaf Mountain (Mt Davidson) to the Red Hill, some two miles ahead of us."29

Campbell does not elaborate what form the signalling took, other than that he "heard" it. This could refer to the crackle of fires, but James Bonner, a Jagera descendant, pointed out to me that many of these lookouts were placed in spots where sound could easily travel a large distance across to other points. Anyone who has visited the lookouts at Springbrook behind the Gold Coast would have experienced how people mumbling one side of the gorge can be clearly heard across the valley at such spots. Thus signalling could occur through the human voice, clapsticks or some other means, and then be relayed to another lookout.

Although some non-aggressive uses of smoke signalling and signalling hills may have been misconstrued by early settlers, it seems likely that signal hills and their codes of signalling were at times applied for defensive and offensive purposes during the Frontier Wars. From our brief examination, it would seem that smoke-signalling was more than sophisticated enough to serve inter-tribal communication and coordination for attacks and speedy retreats. Moreover, there are several early accounts that attest to its use for exactly that purpose.

- Nathan Davies The A-Z of the meanings of South Australia's town names, part two, The Advertiser October 12, 2013 10:30PM

- Joseph Smith, Spitfire Burdekin Expedition, North Australian, Ipswich & General Advertiser, 11 Dec 1860, p 4

- Natives of Yorke's Peninsula - Port Victoria, South Australian Register. 26 December 1840 p 4

- Natives of Yorke's Peninsula - Port Victoria, South Australian Register. 26 December 1840 p 4

- P. Selheim, Treatment of Aborigines, The Courier 5 March 1862 p 2

- To the Editor of the Sydney Morning Herald. The Sydney Morning Herald 30 November 1857 p 8

- Intercolonial News, The South Australian Advertiser 24 December 1861 p 2

- Eli Rhys, Aboriginal Smoke Signals, The Queenslander 10 September 1921 p 11

- Dimon. Australiana -Aboriginal Smoke Signals The World's News (Sydney) 1 May 1929 p 12

- Eli Rhys, Aboriginal Smoke Signals, The Queenslander 10 September 1921 p 11

- Thomas Welsby, Memories of Amity. VII. The Brisbane Courier, 18 June 1921 p 16

- History repeats itself,' The Queenslander, 6 Ap 1901, p 33; J C Bennie, 'The Bunya Mountains - Early Feasting Ground of the Blacks, The Dalby Herald, 1931, p 2

- Bunya Mountains Rangers & Elders Association, personal communication, July 2009

- J C Bennie, 'The Bunya Mountains - Early Feasting Ground of the Blacks,' The Dalby Herald ,1931, p 2

- The Smoke Signals of the Australian Aborigines, South Australian Register, 24 October 1893 p 6

- M E M Tooth, Station Life in the Early Sixties: Wide Bay and Burnett Regions, Gympie Times and Mary River Mining Gazette, 23 December 1909 p 1

- William Clark, Sketcher: Explorer Walker - Organiser and First Commandant of the Native Police Force, The Queenslander 30 November 1912 p 8

- Gaiarbau, in Robin A Wells, In the Tracks of a Rainbow - Indigenous Culture and Legends of the Sunshine Coast Sunshine Beach: Gullirae 2003, 71.

- T. Magarey. Ethnological: Smoke Signals of the Aboriginals, Adelaide Observer, 28 October 1893 p 34

- The Smoke Signals of the Australian Aborigines, South Australian Register, 24 October 1893 p 6

- William Clark, Sketcher: Explorer Walker - Organiser and First Commandant of the Native Police Force, The Queenslander 30 November 1912 p 8

- The Smoke Signals of the Australian Aborigines, South Australian Register, 24 October 1893 p 6

- Gaiarbau, in Robin A Wells, In the Tracks of a Rainbow - Indigenous Culture and Legends of the Sunshine Coast Sunshine Beach: Gullirae 2003, 71.

- Thomas Hall, c.1900 (re-print 1987), A Short History of the Downs Blacks known as 'The Blucher Tribe' Warwick: Vintage/ Warwick Newspapers, 47-8.

- Eli Rhys, Aboriginal Smoke Signals, The Queenslander 10 September 1921 p 11

- Dimon. Australiana - Aboriginal Smoke Signals The World's News (Sydney) 1 May 1929 p 12

- Dimon. Australiana - Aboriginal Smoke Signals The World's News (Sydney) 1 May 1929 p 12

- Dimon. Australiana -Aboriginal Smoke Signals The World's News (Sydney) 1 May 1929 p 12

- John Campbell, 1936, The Early Settlement of Queensland, (Brisbane: Bibliographic Society of Queensland), 19.

Published with permission by the Author on 21 February 2016